by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie”, Anul XV, nr. 72 (4 / 2017) “AFRICA FLUIDĂ“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2017. The author is a member of the International Scientific Board of the magazine

Abstract

Post-September 11th, with its load of upheaval in international law (weakening of state prerogatives, monopoly of warlike operations, consensus on border violations for real or alleged humanitarian offences), has exacerbated hostilities and increased instability of the already weak countries in the area, now even more dependent than before on decisions and actions of the great global players or non-state actors their emissaries. Many analysts glimpse in the new regional policies the danger of a neo-colonialism in the guise of a soft power whose purpose is still functional to the interest of external institutional and economic subjects. Despite set out intentions, G5 Sahel seems focused only on anti-terrorism and security coordination goals, yet, than on socio-economic development.

The “expansive” policies in the Sahel by global and neighbouring regional powers draw the following framework: Russia hired a new role of intervention and mediation; China accepted a role of persuasion (rather than imposition), always under UN auspices and with the consent of regional and national bodies; Algeria, which has always hold an adverse stance to military interventions, and Morocco, which has shown an excellent ability to mobilize financial resources, are in competition for hegemony over the area. Yet another front of interference consists of imported religious movements that are accused of being the “longa manus” of foreign countries and find an easy shore in the Tuareg’s and Arab’s claims.

The U.S. seems to direct its political actions towards strengthening military programs in the region to defend its main energy interests. The EU acts according to the defence of certain values it considers to export (democracy, human rights and the rule of law), establishing a real form of pressure aimed at enforcing political reforms in exchange for conditional economic aid. It weighs on French actions the legacy of Françafrique, i.e. the neo-colonial policy put in place after the season of independences. In the Sahel shadows still stands on the real motivations of the frequent military interventions justified by humanitarian or conflict prevention reasons. It seems evident the Sahel instability and political dependence cannot be overturned only by military-based policies.

Keywords: Sahel, interference, neo-colonialism, anti-terrorism, soft power, governance, Françafrique, military programs, G5 Sahel, Tuareg, Algeria, Morocco.

Dependence and interference

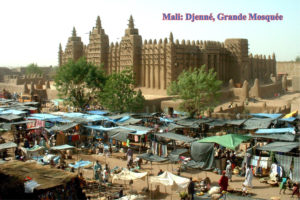

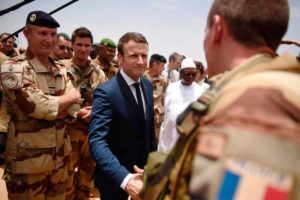

Gao, on the river Niger, is home to the largest French military base outside the national territory. Since April 6th, 2012 to February 14th, 2013, the ancient capital of the Songhai Empire, which introduced Islam there, has been the capital of an independent State of Azawād, a vast territory in northern Mali, afterwards controlled militarily by the French. You can see why Emmanuel Macron, a few days after taking over as President of the French Republic, felt a duty to pay tribute to the 1,600 soldiers quartered in the Sahel heart.[1] This episode is symptomatic of the ancient land fate.

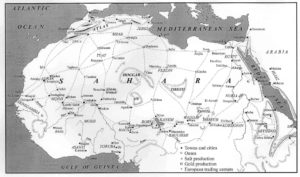

From a geopolitical point of view, the Sahel, one of the poorest areas and with one of the highest demographic growth in the world,[2] exerts a strong attraction both on the great powers and on the neighbouring countries due to the presence of huge energy resources (uranium, oil, minerals) and to its strategic position among the Mediterranean Sea, the Sahara desert and the vast sub-Saharan area. The constant instability of these countries by their independence finds a plausible explanation if these geographical features add some behaviour peculiarities, such as a weak government’s control outside the single capital cities,[3] a frequent leadership’s corruption and a subversive attitude of some endogenous or imported political movements.[4]

As a place of conflict (endogenous or imported ones), Sahel is certainly not alone on the world stage, but post-September 11th, with its load of upheaval in international law (weakening of state prerogatives, monopoly of warlike operations, consensus on border violations for real or alleged humanitarian offences),[5] has exacerbated hostilities and increased instability of the already weak countries in the area, now even more dependent than before on decisions and actions of the great global players or non-state actors their emissaries. The hope (or rhetoric?) of the international community relies on the aggregation ability of Sahel States within a framework of regional alliances. But these ones, if not wisely addressed, are likely to further undermine the sovereign prerogatives of governments and exalt the leading role of the inspirers and financiers of the consequent measures, who are always external to the local realities for obvious reasons of economic power.

All this gives rise to interference allegations actually not certainly a result of these initiatives, considering that Africa as a whole was penalized by a colonial and even post-colonial subjection. Many analysts glimpse in underway and proposed regional policies the danger of a neo-colonialism “with a human face” in the guise of soft power more tolerable by local people and their leaders but whose purpose is still functional to the interest of external institutional and economic subjects. Others look at the content of the measures these initiatives envisage, in order to assess their perspective and foreseeable consequences. In other words, even the overlapping of exogenous decisions on the ones by individual governments could be acceptable if this were congruent and integrative with respect to national interests and especially if aimed at the economic and social development of populations, not only at their home security.

Fig. 5 – Azawād – Map showing the fullest extent of rebel-held territory in January 2013 (by Orionist)

Although the Sahel has not been immune from heinous conflicts and bloody political convulsions, in recent decades the U.S. and France have stressed the need to intervene exclusively by military cooperation programs to eradicate the terrorist threat from the area, and they completely neglect the historical internal causes induced by colonial mismanagement of ethnic integration, political representation and training of independent States.[6] A turning point came in 2012 when a Tuareg uprising in northern Mali made clear that all military programs implemented in the Sahel since 1998 had been ineffective and inefficient. This acknowledgement did not change the militarization policy in the area; in fact, it coincided with the intensification of the foreign military presence, and the involved governments justified it by the urgent need to stem the aggressiveness of political movements deemed jihādists and aligned with al-Qāʿida in the Islamic Maghreb. A shadow of suspicion still stands that sometimes these anti-terrorism measures might serve to support or, conversely, overthrow governments considered to be friends or foes, respectively, influencing the institutional and political destiny of the countries.

Fig. 7 – The UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, with G5 Sahel’s Heads of States, French President Emmanuel Macron, and the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs, Federica Mogherini (UN Photo)

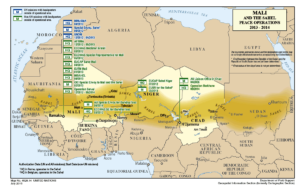

The new security programs

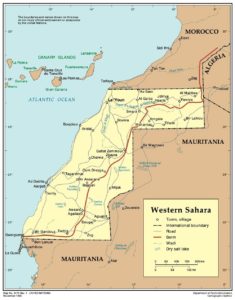

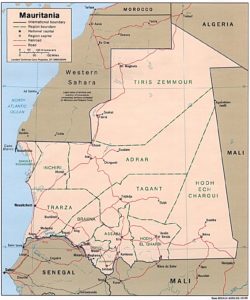

Last June 20th, following the 2013 French occupation of Mali, the UN Security Council adopted the Resolution 2359 requested from Paris,[7] authorizing the deployment of 5,000 G5 Sahel soldiers, additional to the existing forces of cross-border French operation Barkhane,[8] other U.S. and German special forces, Minusma troops (the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali) and the national armies. On July 2nd, the G5 Sahel states (Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Tchad) officially launched the new multinational military force, which will focus on border areas: one along the Niger-Mali border, another between Mali and Mauritania and a third one straddling the borders among Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali.[9]

Fig. 8 – Meeting of the G5 Sahel’s Security Cooperation Platform (PCMS) in Nouakchott, Mauritania, on October 24th and 25th, 2017 (UNODC Photo)

Fig. 9 – Political map of Mauritania (Source: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/)

Fig. 10 – Liptako-Gourma Region (Source: Institute for Security Studies, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-g5-sahel-must-do-more-than-fight-terror)

The institutional coordination framework called G5 Sahel, with its permanent Secretariat in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, was born in February 2014 when the five countries met in Nouakchott at a summit for regional cooperation on security and development with the political, financial and technical support of France and the EU. Three years later, the extraordinary February summit in Bamako announced the intention to create a joint anti-terrorism military force and the running joint patrolling in the Liptako-Gourma Region.[10] Next April, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council, its executive body, authorized the creation of a joint military force of 5,000 men for an initial 12-month period.[11] Then, the aforementioned UN Security Council Resolution.

Despite the intentions set out in its convention, G5 Sahel seems focused only on anti-terrorism and security coordination goals, yet, according to its main financiers’ needs and settings (first of all, the 2013 French White Paper on Defence and National Security). Thus, the need to improve governance and pursue the socio-economic development of the area is relegated to complement purposes, also because the urgency to block the African migratory wave towards Europe is experienced as a security emergency and little space leaves for elaborate on migration causes and rebalancing measures to be adopted on the spot (Lebovich, 2017). However, the Alliance for the Sahel[12] opened a window for development cooperation in the region, as it promotes joint actions by the EU, its member states, the World Bank Group, the African Development Bank and the UN.[13]

Yet, the basic financial resources for the new military force (probably headquartered in Sévaré, a city in south-eastern Mali) are considerable: they are estimated at US$ 423 million merely in the first year of operations.[14] EU has pledged € 50 million for starting operations and France has promised € 8 million for logistic support. At the recent summit hosted by Macron in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, near Paris, Saudi Arabia said it will contribute € 100 million and UAE offered € 30 million. The U.S.[15] has promised Macron US$ 60 million,[16] while the UK has refused to finance the initiative. Each of G5 Sahel members will contribute € 10 million, but their governments are already financially burdened.[17]

Regarding interference in the internal affairs of the Sahel states, we will consider not only turn-out or military interventions from time to time the countries with on-site security interests launched, but also all forms of economic and financial control and political pressure on institutions, anyhow affecting local governments will. Similar forms of control may target non-institutional subjects playing important (favourable or contrary) roles in dealing with governments. In other words, it’s about widening the scope far beyond the imposition by force, but by that “soft power” mentioned in the opening. Often, wise use of the aid provided to a country can make it meek and willing to perform specific proxy tasks in international contexts or even to assume the role of a “de facto” protectorate. Of course, a judgment is not easy to make and certainly, we will refrain from doing so. However, the contours can be outlined by recording the facts.

Before looking over supposed interference by Western partners in the internal affairs of Sahel countries, a framework of some so-called “expansive” policies by other global and neighbouring regional powers is drawn.

Russia

The Russian Federation plays a limited role in the Sahel, but the new task of intervention and mediation Putin hired in the Middle East has prompted Moscow to seek alliances also in North Africa, paying attention to the Mediterranean shores and the countries allegedly affecting Sahel geopolitical and economic arrangements. It did so primarily by supporting the Egyptian regime of ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ as-Sīsī and in Libya, the Field Marshal Khalīfa Belqāsim Ḥaftar and the Council of Deputies sitting in Tobruk.[18] On the other hand, Moscow had already had a special feeling with the Qaddāfī regime and certainly not for an Islamist danger.

Discreetly maintained for the “status quo” during the Arab revolutions, the Russian Federation has tightened relations with Algeria through the Sonatrach-Gazprom cooperation agreement on hydrocarbons exploration and production in the Berkine basin (close to the Tunisian border), that was signed in 2009 as part of a strategic partnership launched in 2001.[19] In 2014, the Russian Rosatom State Atomic Energy Corporation signed a memorandum of mutual assistance with relevant Algerian authorities, and two years later did so with the Tunisians’.[20] But Russian biggest aid to Algeria (which Algiers must be grateful to) is a partial US$ 4.5 billion debt offset through Russian weapons purchase, which contributed to recovering in Moscow the same role in the armaments sector the USSR had during the Cold War, especially over Algeria, Egypt and Libya. In 2008 Russia had cancelled the US$ 4 billion debt to Qaddāfī’s Libya by the same settlement agreement (Facon, 2017).

Anyway, this Moscow activism in the region emphasizes Putin’s back on the Mediterranean shores with a clear design of obtaining a return in terms of political-economic loyalty and as a resulting international reference point for an Algiers-Tobruk-Cairo axis.

China

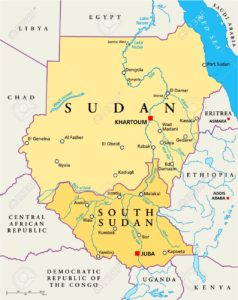

Fig. 14 – Political map of Sudan and South Sudan (Source: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/ 885206811320254465)

The most apparent Chinese presence in the Sahel is not so much of a military nature, rather displayed in the energy sector. Beijing had started a partnership with Kharṭūm for developing its oil industry in 1997,[21] shortly before the theologian Ḥasan ‘Abd Allāh et-Turabi had been removed from the institutional offices.[22] Moreover, Sudan had still been under U.S. sanctions and since 1983 in the grip of a bloody civil war. China National Petroleum Corporation had nevertheless operated colossal investments and found little market competition.

Following January 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the government and the Sudan Liberation Movement ending the second civil war and establishing a legal basis for an independent South Sudan, in 2008 Beijing was quick to open its own consulate in Djuba, considering that 75% of oil wells were located right in South Sudan, although most of the refineries are still in the North. After China recognised the Djuba independence gained in 2011, it held close relations with both countries, because South Sudan landlocked layout forced it to depend on the Kharṭūm government for shipping its oil to Port Sudan, on the Red Sea, through the network of Sudanese pipelines. Since 2013, Chinese interests in oil production have been at risk due to the civil war in South Sudan.

Just the South Sudan issue contributed to relaxing the strict Beijing hands-off policy up to then,[23] especially when it decided to become a member of the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (JMEC) established by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the supervisory body of the 2015 Addis Ababa Peace Agreement.[24] In practice, it has since accepted a role of persuasion (rather than imposition) under UN auspices and with the consent of regional and national bodies, mainly during humanitarian crises. Sure, its military naval base in Djibouti[25] seems to serve more its own geopolitical and commercial interests than conciliation of disputes, mostly when it highlights the unavoidable competition with other two important naval bases established just in Djibouti: the US and the Japanese ones. But who said they must manage a monopoly in this area?

Fig. 17 – Political map of Tchad (Source: https://nl.dreamstime.com/royalty-vrije-stock-foto-tsjaad-image6306585)

China holds a similar approach in other Sahel crises.[26] While giving up a stance on only funding and supporting UN missions, since 2015 Beijing has offered its troops to the Minusma. Of course, its policy of penetration into the Sahel does not go through a sporadic military presence. The Chinese leadership bases its foreign policy in the region (as elsewhere in Africa) on partnerships, on the one hand, helping states to reduce individual national debts, and on the other paving the way for Chinese concessions in the field of natural resources and for performing Beijing investments in particular in the infrastructure sector where the Sahel highlights huge deficiencies. A “win-win” strategy that complies with sovereignty and solidarity concepts (Antončić, 2017). A good example is the relationship China has established with Tchad since 2006, the year mutual diplomatic relations have been restored.[27] Obviously, the Asian giant expects a return of positive image from N’Djamena, as well as all the capital cities of the African partner countries, but also their commitment by its side in international matters.

North-African regional powers and imported religious movements

The North African country most interested in the Sahel affairs is definitely Algeria, which is concerned about its security. However, Algiers has always held a stance averse to military interventions on sovereign territories, both for itself and the world powers,[28] and has been consistent with its Constitution rules,[29] its own history as a victim of European colonial actions, and its historical role of an active member of Non-Aligned Movement, which to date adheres to.[30] For example, it opposed NATO intervention in Libya on the grounds that the Libyan Revolution relates to an internal problem; and, as early as 2012, it had warned France not to invade Mali, fearing terrorist repercussions on its territory, duly it suffered after French intervention of the year after (Porter, 2015).

The Algerian political action, although its military budget has steadily increased since 2011, has nevertheless been focused on expanding trade with the Sahel countries on a basis of bilateral agreements aye in the institutional framework of African Union principles; also because it’s well aware of resulting, together with Morocco, the strongest economy in the area in terms of foreign investments (Lebovich, 2017). On the other hand, security concerns inside and outside its borders prompted Algeria to promote the following initiatives, which might entail military operations, albeit in accordance with the involved countries and within the framework of regional cooperation authorized by the appointed international organizations:

- The Comité d’État-major Opérationnel Conjoint (CEMOC), a liaison body among the military chiefs of Algeria, Mali, Mauritania and Niger with the task of monitoring and intervening on a 2,000-long km and 1,000-deep km trans-border area. Not by chance the Committee is based on Tamanghaset, the most important site of the Algerian Tuareg;[31]

- The Nouakchott Process, born in March 2013 and resulted in December 18th, 2014 in the Nouakchott Declaration for strengthening regional cooperation in security, signed by Burkina Faso, Tchad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Algeria, Libya, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Guinea and Nigeria under African Union aegis.[32]

All in all, these initiatives reflect the same pattern as other non-African initiatives, such as previously exposed G5 Sahel. But we cannot forget Algiers commitment to the May-June 2015 Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali (today stalled, yet),[33] which unveiled Algeria as a leading country in the regional mediation among states and among local non-state organizations.[34]

Algiers also cares very much for its sovereignty and non-interference in its internal affairs. For example, it did not hesitate to deploy tens of thousands soldiers on the Libyan border during the 2011 Revolution, fearing spillover effects on its territory. Similarly, Algeria is not a member of the World Trade Organization[35] because, among other things, it has opposed the body’s request to allow alcoholic products import, which would infringe the Islamic principles of its population.[36]

The actual Algerian diplomatic problem in the Sahel is the rivalry with the Kingdom of Morocco, which gives rise to real competition for hegemony over the area. The Africa Lion 2015[37] has raised serious concerns in Algiers because it feels that Rabat-Washington ties got stronger and rebounds on the international legal position of Western Sahara. But their antagonism goes beyond this specific long-standing issue and affects competition for investments in this area, where Morocco has set up great political and commercial relations with Mali and Senegal and has shown an excellent ability to mobilize financial resources in the banking, telecommunications and air transport (Lebovich, 2017).

The contrast opposing Algeria and Libya to control the Sahel falls within the same case, at least until the Qaddāfī’s drop and the Libyan state disintegration.[38] The allegations to the two nations were that Qaddāfī aspired to the sponsorship of all Tuareg claims in Mali, in order to add another piece to his project of Popular and Social League of the Great Sahara Tribes to bring together the leaders of 21 North African and Middle Eastern desert countries; and that the Algerian behaviour would reveal the purpose to regard the Sahel as the “trash can” home to confine all its internal elements of insecurity (e.g., the Organization of al-Qāʿida in the Land of the Islamic Maghreb – AQIM and the Movement for Unity and Jihād in West Africa – MUJWA).

The focus, as we can see, was and is today on Northern Mali, especially on Tinbuktu, Gao and Kidal territories, due to their huge reserves of oil and gas not yet exploited and on which the state-owned Algerian oil and gas company Sonatrach has significantly invested. On the other hand, since 1998 Qaddāfī had already staked a claim on an instrument of financial-political control over the Sahel, by inspiring the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD) aimed at establishing a vast free trade area in North Africa (but excluding Algeria). Today, the Libyan Field Marshal Ḥaftar seems to have such a more limited aspiration over Tchad and Niger (Lebovich, 2017).

Yet another front of interference consists of non-state organizations, i.e. imported religious movements such as NGOs, charitable organizations and movements of preaching and conversion. This phenomenon was and is widespread in Northern Mali as a subsidiary element to shortcomings of the State, which, conversely, has been imposing martial law on that land for decades. In practice, this void has been filled by various Islamic organizations of Asian origin and with very different conceptions compared to Saharan syncretism. The latter has been forming over the centuries with a Sufi contribution to the endowment of an Islamic identity peculiar to these lands (Chauzal e van Damme, 2015). The religious history of the Sahel is very complex, and here you cannot help but refer to the experiences of the various Sufi brotherhoods that have affected the Sahel.[39] Each of them has an influence in terms of spiritual attraction, which is used in terms of cultural and political gravitation by countries regarding themselves its progenitors or today’s patrons.

The current problem for local governments arises from a new presence of religious movements that are accused of being the “longa manus” of foreign countries (such as Libya, Saudi Arabia, some Gulf Emirates and even Pakistan). These movements aim to exert their influence on the territory and find an easy shore in the Tuareg’s and Arab’s claims for federalism (Popular Front of Azawād) or an Islamist autonomy (High Council for the Unity of Azawād) or an Islamic jihād (ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn). Thus, the problem would lie in the foreign nature of those inspirational movements and not in their message. But the so-called “Western” states reversed the problem because the connivance of those movements with foreign countries is not easy to prove on an international level (also because it would involve friendly countries and allies), while they could be more easily attacked by military actions and resorting to the danger of Islamic radicalism. Overall, a huge headache!

Out of the way autonomist and federalist aggregations, seemed to be a Malian internal issue, Western interventionism has therefore concentrated on some of the aforementioned groups (AQMI, MUJWA and ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn), which have however formed locally, and on others that are actually ethero-inspired, such as:[40]

- The Deobandi Tablighi Jamā‘at (Group for the Diffusion of Faith), a 1926-born pacifist trans-national missionary movement originated from India and active in Northern Mali since the ’90s of the last century;

- The Saudi-inspired Wahhābis of the Gao-based Signed-in-Blood Battalion, founded in 2012 by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the former Algerian Commander in the Sahara-Sahel of an independent group of al-Qāʿida in the Islamic Maghreb.

United States

In recent years, the U.S. seems to rediscover the Sahel strategic importance and directing its political actions towards strengthening military programs in the region to defend its main energy interests.[41] The U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of African Affairs bases its policies on the following four priority guidelines:[42] strengthening democratic institutions; supporting African economic growth and development; advancing peace and security; promoting opportunity and development.

If well as just the first step would sound at odds with alleged French requirements to determine the leadership of the francophone nations deemed improperly within the competence of France on the basis of its role as a former colonial power.[43] Examples of this are French support to the 2012 coup against President of Mali Amadou Toumani Touré, regularly elected in both 2002 and 2007 polls, and the defence of the new coup regime established in Bamako when the Tuaregs of ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn declared the independence of Azawād. The reaction would have been the subsequent French military intervention a year later by Operation Serval. Hard to argue that this intervention was carried out to strengthen democratic institutions.

The military and economic aid programs launched by the U.S., which did not fail to encourage local political repressions by local governments, have been:

- The Pan-Sahel Initiative, established in November 2002, made operational in late 2003 and aimed at fighting terrorism in Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Tchad and protecting their borders;

- The Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Initiative of 2004 and Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership a year later, expansions of the previous initiative also to Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Senegal and Nigeria and today widened to Libya and Burkina Faso.

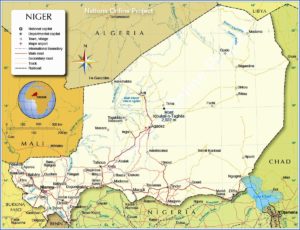

Since October 1st, 2008, this program is placed under the responsibility of the U.S. Africa Command.[44] Just in the Sahel, taking into account co-operative security positions, advanced operational headquarters and other military departments, the U.S. is present in Burkina Faso, Tchad, Mali, Niger and South Sudan. Niamey, in Niger, is one of the most important bases, and that one in N’Djamena, in Tchad, has been frequently used for military operations against Boko Haram.

Besides these programs involving mainly military intervention on site, there are others managed by AFRICOM for military training, the sale of weapons and so on, such as among others:

- The African Contingency Operations Training and Assistance(ACOTA), as part of the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), with Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania and Niger as its partners in the Sahel;

- The Foreign Military Sales Program, with Mali as its partner in the Sahel;

- The Africa Regional Peacekeeping (ARP) Liaison with African “peacekeeping” military commands, with Mauritania, Western Sahara, Niger, Tchad and Sudan as partners in the Sahel;

- The Security Governance Initiative, with Mali and Niger as partners in the Sahel.[45]

European Union

The EU grounds its policy in the region on the Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel, adopted in 2011,[46] and the Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-2020, adopted in 2015.[47] It has identified four lines of action: development, good governance and resolution of internal conflicts; political and diplomatic action; security and rule of law; contrast to violent extremism and radicalisation.

Since 2007 it has launched the following military or civil missions:

- EUFOR Tchad (a military mission made operational in 2008 and dissolved in 2009 when Minurcat UN mission took over the European force);

- EUCAP Sahel Niger (EU Capacity Building Mission in Niger, a civil operation adopted in 2012 and still in progress);

- EUTM Mali (EU Training Mission in Mali, a military operation established in 2013, made operational in 2016 and still in progress);

- EUCAP Sahel Mali (a civil mission decided in 2014, started in 2015 and still ongoing).

In addition to various regional development cooperation initiatives (some financed through its European Development Fund), in 2001 the EU also launched an Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative,[48] within the framework of its Generalised System of Preferences (GSP),[49] which favours imports from least developed countries (in our case all the Sahel countries), which are exempt from customs duties and without quotas; in 2014 the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP)[50] to provide funds for conflict prevention and pre- and post-crisis; and in 2015 its Programme of support for enhanced security in the Mopti and Gao regions and for the management of border areas (PARSEC Mopti-Gao),[51] as annexed to the establishment of EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa to address migratory crises in the region of Sahel / Lake Tchad, the Horn of Africa and North Africa.[52]

A feature of EU foreign policy (especially to the Sahel countries) is the defence of certain values it considers to export: democracy, human rights and the rule of law. In particular, the EU has the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR),[53] implementing art. 21 of the Treaty on European Union.[54] Without questioning the nobility of purpose, one cannot but emphasize that this is a real form of pressure (if not an interference in the decision-making) because it’s aimed at enforcing political reforms in exchange for conditional economic aid. By not adhering to the political “suggestion”, a candidate country must give it up.[55] Of course, the migration crisis could reverse the roles…

France

For some, the French legacy in the Sahel is an opportunity, for others a problem. The current issue is not so much a historical judgment on its colonial presence, as an assessment of how its post-colonial presence has been carried forward. But France itself realized the impossibility of keeping 36,000 soldiers away from the metropolitan ground due to the high operating costs of permanent stationing and continuous operational missions promoted locally.[56] The costly defence agreement signed with Mali after the French occupation of the north in 2013 has probably made it clear in Paris. It was the time the financial burden of so-called anti-terrorist operations in the Sahel to be distributed among its European allies, perhaps in return for the transfer of a piece of its political-economic influence, however illusory in the eyes of wise analysts. Also because the failure of UN Minusma peacekeeping mission in Mali (more than one hundred Blue Helmets have been killed there) (Busch, 2017) made clear a need to widen the perspective to a regional dimension. This explains the launch of the G5 Sahel initiative, which has been widely talked about at the beginning, and why a month after President Macron took office at the Élysée Palace, the UN Security Council (of which France is an authoritative member with veto power) has authorized the joint military force linked to the initiative.

But Paris still has an opacity problem in its foreign policy. It weighs on its actions the legacy of Françafrique, i.e. the neo-colonial policy put in place after the independence season of the countries previously belonging to its colonial empire, to keep an influence on them through political, economic and military relations not always transparent and presumably parallel to the governments in office.[57] In the Sahel, however, shadows still stand on support for the past military dictatorships in Tchad and those on the real motivations of the frequent military interventions justified by humanitarian or conflict prevention reasons.

These true or presumed allegations do not change the historical context of hostilities and military assistance programs in the Sahel, including:

- The operations Épervier (Sparhawk) in Tchad since 1986 and Serval in Mali in 2013, which were replaced in 2014 by the aforementioned Barkhane cross-border operation, strong of 4,000 men and based in N’Djamena, Tchad;[58]

- The Reinforcement of African Capacity to Maintain Peace (RECAMP) initiative, which began in 1997 to improve the military abilities of African troops involved in peacekeeping operations;[59]

-

Fig. 25 – Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) – Demonstrations against then-President Blaise Compaoré in October 2014

The Sahel three-year plan[60] launched in 2009 for Niger, Mauritania and Mali and which formed the model for the EU Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel (Busch, 2017);

- The Sabre secret operation (sometimes recognized at times denied by France), started in November 2009 in Atar, Mauritania, continued in January 2010 to Mopti, Mali, and in 2011-14 permanently installed in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, with extensions in Niger, Mauritania and Mali.[61]

It’s no secret to anyone a major French interest in the Sahel lies in the uranium production, all concentrated in Niger, particularly in the Arlit area, just 170 km from the Algerian border. France imports from Niger 40% of its energy needs (hinging on nuclear energy) and Niger is the third largest producer of uranium in the world, after Canada and Australia. Everything following the classic rules of supply and demand, then. But the problem is the profits of Areva, the French State-controlled multinational concessionaire of Arlit mining, are more than twice the Niger GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund.[62]

Fig. 28 – Political map of Niger (Source: https://www.globalresearch.ca/hybrid-war-can-wreak-havoc-across-west-africa-3/5590166)

Hard to argue this monopoly does not create a political dependency of the African state, which is the second-last country of the world (before the Central African Republic) in the 2015 ranking of the UN Human Development Index,[63] and where more than 60% of the population live with less than a dollar a day. Difficult, too, it does not imply French military operations in the Sahel deal with the protection of valuable specific interests, rather than Islamic extremism and human rights. All, however, according to the principles established by the bilateral decolonization pacts, which allow Paris to intervene at the request of the “friendly” francophone countries and keep its military bases. The historical resistance of some of these countries (and among them, coincidentally, just Mali!) have been useless, because the shadow of a coup “in defence of democracy” is always around the corner, as shown by the Sahel events of the last 50 years.[64]

Conclusion

It seems evident the Sahel instability and political dependence cannot be overturned only by military-based policies, also because in the past they have failed to reach their goals. The problems must be identified in the infringement of the principles enshrined in the UN the World powers had fashioned in terms of balance; and even earlier, in the infringement of the Atlantic Charter principles the “Western” powers had wished to base their behaviour.[65]

Today, with the run-up to new world order, those principles seem to be delegitimized, a purely intellectual exercise, subordinated to the national interests of the super-powers, which this way pursue once again (more than 130 years after the Berlin Conference’s directions) domination over their areas of influence. In the name of radicalization in progress, the watchwords have again become America First or grandeur, but human rights! And the UN itself is about to be delegitimized by the radicalisation of the major power, which today weakens it in financial terms. All this is hypocritically motivated and validated (even in the public opinion) as a primary (and indeed exclusive) need of security and fight against indefinite terrorism (any Chancery states: the terrorist is who I say!)

The analysis is useless if not accompanied by feasible indications of perspectives that, as already seen in this text, are not lacking in the intentions expressed in relevant documents and nevertheless are little practised in reality. In the case of the Sahel, it would therefore take into account at least the following issues:

- Political dynamics and decisions on economics and investment field are a prerogative of individual states while hoping forms of coordination at the regional level and provided that it avoided any interference in the internal affairs in the shadow of international initiatives for purposes running counter to the area interests;

- Pursuing an approach to policies spatially and sectorally coordinated might prevent negative effects resulting from investments over a single target (the enhancement of security, in this case), due to obvious aftermath biases and poor performances of cost/benefit indices;

- More consideration of mutual diplomatic relations among states and between them and the regional powers influencing them in many ways might improve the implementation of initiatives aimed at internal and external overall security;[66]

- Taking into account the regional concerns towards initiatives deemed as led from outside might mitigate declared or implied contrast to the initiatives themselves.[67]

It would be the beginning of a virtuous path all the Sahel requires, and on which, if not its redemption, at least a hope of survival is based.

[1] Romain Herreros (19/05/2017). Au Mali, Macron veut “accélérer”, “sans barguigner”, contre les jihadistes. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2017/05/19/emmanuel-macron-sur-la-base-militaire-de-gao-au-mali_a_22098936/

[2] The World Bank ranks all countries in the area as low or medium-low income (up to US$ 4,000 per capita annually) and with a population increase of more than 100% in the period 1960-2015. Retrieved from The World Bank, WDI 2017 Maps, https://data.worldbank.org/products/wdi-maps.

[3] Mark Vincent Abdilla (August 25th, 2014). American Presence in Africa: Military Intervention in Somalia and the Sahel, University of Malta, Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies, p. 57.

[4] Andrew Lebovich (July 2017). Bringing the Desert Together: How to Advance Sahel-Maghreb Integration, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), London (UK), p. 2.

[5] Taylor B. Seybolt (2007). Humanitarian Military Intervention. The Conditions for Success and Failure. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Solna (Sweden), p. 1.

[6] Grégory Chauzal and Thibault van Damme (March 2015). The roots of Mali’s conflict. Moving beyond the 2012 crisis, Clingendael, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Conflict Research Unit (CRU) Report, The Hague (Netherlands), pp. 43-48.

[7] Ahmedou Ould – Abdallah (June 30th, 2017). France G5 Sahel Summit in Bamako. Retrieved from Centre for Strategies and Security for the Sahel Sahara,

http://www.centre4s.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=184:france-g5-summit-in-bamako-&catid=39:article.

[8] Started in 2014 following the end of the French operations Épervier (Sparhawk) in Tchad since 1986 and Serval in Mali since 2013.

[9] French and West African Presidents Launch Sahel Force (July 03, 2017). Retrieved from http://uhuruspirit.org/news/?x=10483#.WjlJudLia70.

[10] Patrolling is under the control of the Integrated Development Authority of the Liptako-Gourma Region, which was dominated by the Islamic State of Fulani ethnicity two centuries ago.

[11] The related mandate included: combating terrorism, drug trafficking, and human trafficking; contributing to the restoration of state authority and the return of displaced persons and refugees; facilitating humanitarian operations and the delivery of aid to affected populations as much as possible; and contributing to the implementation of development strategies in G5 Sahel countries. Retrieved from August 2017 Monthly Forecast (July 31st, 2017), http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2017-08/sahel_2.php.

[12] A joint initiative of France, Germany and the EU, launched in Paris on July 13th by President Macron and Chancellor Merkel.

[13] The French Development Agency is expected to provide € 200 million in aid for an Alliance initiative called Tiwara. Retrieved from Elena Blum (14.07.2017), «Nous voulons montrer aux populations du Sahel qu’une action publique est entreprise pour eux», http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2017/07/14/nous-voulons-atteindre-les-populations-du-sahel-et-leur-montrer-qu-une-action-publique-est-entreprise-pour-eux_5160756_3212.html.

[14] ‘UN Should Do Its Best to Find Money’ for New Army in Africa – Libyan Politician (05.11.2017). Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/analysis/201711051058836455-libya-migration-crisis-sahel-army/

[15] The US contributes to the extent of 28-32% of the budget of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Retrieved from A. Ould – Abdallah (June 30th, 2017), France G5 Sahel Summit in Bamako, cit.

[16] S. Arabia pledges $100 million and UAE $30 million for Sahel anti-terror force (December 13th, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.france24.com/en/20171213-africa-counter-terrorism-sahel-saudi-arabia-pledges-100-million-uae-g5-macron.

[17] Tchad, Burkina Faso and Niger have deployed about 4,100 soldiers in the Minusma, which has 12,000 on the field. Niger and Tchad also supply troops to a similar regional force settled by Tchad Lake Basin countries to fight the Boko Haram militants in Nigeria. Tchad, which has the most efficient armed forces in the region but also face economic difficulties arising from the recession, has expressed reluctance to further engage its troops unless they receive more international support. Retrieved from August 2017 Monthly Forecast (July 31st, 2017), cit.

[18] Isabelle Facon (July 2017). Russia’s quest for influence in North Africa and the Middle East. Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Observatoire du monde arabo-musulman et du Sahel, pp. 3-14.

[19] Gazprom International completes exploration in Algeria (April 29th, 2016). Retrieved from http://www.gazprom-international.com/en/news-media/articles/gazprom-international-completes-exploration-algeria.

[20] In the face of these economic partnerships, Moscow provides training in counter-terrorism in Algeria, as it does in Tunisia.

[21] China’s Foreign Policy Experiment in South Sudan (July 10th, 2017). Retrieved from International Crisis Group, Report N° 288 / AFRICA, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/south-sudan/288-china-s-foreign-policy-experiment-south-sudan.

[22] Turabi, who at the time was President of the Sudanese Parliament and had given a hard time to the Washington-Riyāḍ axis, had come up against President Bashir on the extent of the presidential powers.

[23] The non-intervention meant for Beijing not determining or supporting regime changes and unilateral military operations or, in any case, interference in matters of internal governance. Retrieved from China’s Foreign Policy Experiment in South Sudan, cit.

[24] IGAD (August 17th, 2015). Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan. Retrieved from http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/documents/IGAD-Compromise-Agreement-Aug-2015.pdf.

[25] Since July 2017 inauguration this base has been managed by the People’s Liberation Army Navy.

[26] Diego Antončić (2017). The EU and China in the Sahel: Similarities in Challenges and Differences in Visions, in EU-China Observer, Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies, n. 3.17 Exchanging Ideas on EU-China Relations: An Interdisciplinary Approach, pp. 12-15.

[27] In return for the investment in the oil industry, road and airport, Beijing has expressed its willingness to intervene by aid in the areas of basic and scientific education and medical assistance. Retrieved from Chad – China Relations (31-10-2016), https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/africa/cd-forrel-prc.htm.

[28] Geoff D. Porter (2015). Questioning Algeria’s Non-Interventionism. Institut Français des Relations Internationales (IFRI), Politique étrangère 3:2015 Focus | Algeria, a New Regional Power?, p. 1.

[29] Constitution de la République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire (December 8th, 1996), Chapitre III L’État, art. 26. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_125825.pdf

[30] Non-Aligned Movement, Centre for South-South Technical Cooperation (latest reference on December 31st, 2017). NAM Member Countries. Retrieved from http://csstc.org/v_ket1.asp?info=11&mn=1.

[31] Au cœur du Cemoc à Tamanrasset (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.liberte-algerie.com/reportage/au-coeur-du-cemoc-a-tamanrasset-96574/print/1.

[32] African Union Peace and Security (December 19th, 2014). Nouakchott Declaration of the 1st summit of the countries participating in the Nouakchott process on the enhancement of security cooperation and the operationalization of the African Peace and Security Architecture in the Sahelo-Saharan Region. Retrieved from http://www.peaceau.org/en/article/nouakchott-declaration-of-the-1st-summit-of-the-countries-participating-in-the-nouakchott-process-on-the-enhancement-of-security-cooperation-and-the-operationalization-of-the-african-peace-and-security-architecture-in-the-sahelo-saharan-region.

[33] Arthur Boutellis and Marie-Joëlle Zahar (June 2017). A Process in Search of Peace: Lessons from the Inter-Malian Agreement, IPI, International Peace Institute, New York, pp. 12-21.

[34] G. Chauzal and Th. van Damme (March 2015). The roots of Mali’s conflict, cit., p. 54.

[35] World Trade Organization (latest reference on December 31st, 2017). Members and observers of the WTO. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/org6_map_e.htm.

[36] G. D. Porter (2015). Questioning Algeria’s Non-Interventionism, cit., p. 3.

[37] Military exercise sponsored by the U.S. Africa Command and led in Morocco by the Marine Corps Forces Europe and Africa. Retrieved from United States Africa Command (n.d.), African Lion, http://www.africom.mil/what-we-do/exercises/african-lion.

[38] G. Chauzal and Th. van Damme (March 2015). The roots of Mali’s conflict, cit., pp. 22-29 and 43-47.

[39] E.g., Shādhiliyya and Idrīsiyya of the Berber Ṣūfī from Morocco, Darqawiyya and Alawiyya from Morocco and Algeria, Rahmaniyya from Algerian Kabylia, Sanūsiyya from Libya and Sahel, Sammāniyya from Sudan, Tijāniyya from West Africa and Sudan and of its Toucouleur Empire, Murīdiyya from Senegal and Gambia and the influence of a host of Sufi brotherhoods born in Egypt. Retrieved from Glauco D’Agostino (June 2010), Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre, Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

[40] Glauco D’Agostino (January 25th, 2014). The Tuareg’s Hope and Great Patience. For Now… Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/tuaregs-hope-great-patience-now/

[41] M. V. Abdilla (August 25th, 2014). American Presence in Africa, cit. p. 7.

[42] Marco Massoni (2016). Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa, in Ministero della Difesa, Centro Militare di Studi Strategici (CeMISS), Osservatorio Strategico, Year XVIII, issue VII, p. 66.

[43] Gary K. Busch (June 29th, 2017). The U.S. and the wars in the Sahel. Retrieved from https://www.pambazuka.org/human-security/us-and-wars-sahel.

[44] Unified Combatant Command based in Stuttgart (Germany), responsible for U.S. relations and military operations throughout the African continent, excluding only Egypt.

[45] The White House (August 6th, 2014). Fact Sheet: Security Governance Initiative. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/08/06/fact-sheet-security-governance-initiative.

[46] European Union External Action Service (June 21st, 2016). Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel. Retrieved from

https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/strategy_for_security_and_development_in_the_sahel_en_1.pdf.

[47] Council of the European Union (April 20th, 2015). Council conclusions on the Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-2020. Retrieved from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21522/st07823-en15.pdf.

[48] D. Antončić (2017). The EU and China in the Sahel, cit., p. 13.

[49] European Union (December 19th, 2017). Generalised System of Preferences (GSP). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/development/generalised-scheme-of-preferences/

[50] European Commission (n.d.). The Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sectors/human-rights-and-governance/peace-and-security/instrument-contributing-stability-and-peace_en.

[51] European Commission (June 13th, 2016). Programme d’Appui au Renforcement de la Sécurité dans les régions de Mopti et de Gao et à la gestion des zones frontalières (PARSEC Mopti-Gao). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/t05-eutf-sah-ml-2016_fr.pdf

[52] European Commission (December 18th, 2017). EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/eu-emergency-trust-fund-africa-20171218_en.pdf.

[53] European Commission (n.d.). The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights. Retrieved from http://www.eidhr.eu/

[54] Official Journal of the European Union C 326/13 (26.10.2012). Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union, Title V, Chapter 1 General Provisions on the Union’s External Action, Article 21.

[55] D. Antončić (2017). The EU and China in the Sahel, cit., p. 14.

[56] G. K. Busch (June 29th, 2017). The U.S. and the wars in the Sahel, cit.

[57] For example, many rumours have foreshadowed past patronage relationships and networking to provide financing French political parties.

[58] A. Ould – Abdallah (June 30th, 2017), France G5 Sahel Summit in Bamako, cit.

[59] Andrea de Guttry, Emanuele Sommario and Lijiang Zhu (2014). China’s and Italy’s Participation in Peacekeeping Operations, Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland (USA), p. 165.

[60] Christopher S. Chivvis (2016). The French War on al Qa’ida in Africa, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY (USA), pp. 45-46.

[61] Yanis Thomas (March 10th, 2015). Les Opérations Sabre et Barkhane en violation de la Constitution. Retrieved from https://survie.org/billets-d-afrique/2015/243-fevrier-2015/article/les-operations-sabre-et-barkhane-4908.

[62] Julia Hahn (May 28th, 2014). Niger sets new terms in uranium ore deal with Areva. Retrieved from Deutsche Welle, http://www.dw.com/en/niger-sets-new-terms-in-uranium-ore-deal-with-areva/a-17667618.

[63] United Nations Development Programme (n.d.). Key to HDI countries and ranks, 2015. Retrieved from Human Development Report 2016, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/rankings.pdf.

[64] Among others, we recall the coups in Upper Volta 1966, Mali 1968 and 2012, Tchad 1975 and 1990, Burkina Faso 1983 and 1987, Niger 2010 and Mauritania since 1978 onwards with as many as six coups.

[65] Among others, there are a ban of territorial adjustments against the wishes of concerned peoples; a right to people’s self-determination; the abatement of trade barriers; global economic cooperation and advancement of social welfare; a world free of want and fear; freedom of the seas; disarmament of aggressor nations and common post-war disarmament.

[66] For example, this is the case of the existing mistrust between Mali and Burkina Faso because of past local wars (those of 1974 and 1985), and between Morocco and Algeria over the situation in Western Sahara.

[67] It’s the case of Algeria towards G5 Sahel, deemed as a regional clustering inspired by France, the former colonial power, still the prime reference for West African countries.

References

- Abdilla, Mark Vincent (August 25th, 2014). American Presence in Africa: Military Intervention in Somalia and the Sahel, University of Malta, Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies.

- Antončić, Diego (2017). The EU and China in the Sahel: Similarities in Challenges and Differences in Visions, in EU-China Observer, Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies, n. 3.17 Exchanging Ideas on EU-China Relations: An Interdisciplinary Approach.

- Au cœur du Cemoc à Tamanrasset (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.liberte-algerie.com/reportage/au-coeur-du-cemoc-a-tamanrasset-96574/print/1.

- August 2017 Monthly Forecast (July 31st, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2017-08/sahel_2.php.

- Blum, Elena (14.07.2017). «Nous voulons montrer aux populations du Sahel qu’une action publique est entreprise pour eux». Retrieved from http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2017/07/14/nous-voulons-atteindre-les-populations-du-sahel-et-leur-montrer-qu-une-action-publique-est-entreprise-pour-eux_5160756_3212.html.

- Boutellis, Arthur and Zahar, Marie-Joëlle (June 2017). A Process in Search of Peace: Lessons from the Inter-Malian Agreement, IPI, International Peace Institute, New York.

- Busch, Gary K. (June 29th, 2017). The U.S. and the wars in the Sahel. Retrieved from https://www.pambazuka.org/human-security/us-and-wars-sahel.

- Chad – China Relations (31-10-2016). Retrieved from https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/africa/cd-forrel-prc.htm

- Chauzal, Grégory and van Damme, Thibault (March 2015). The roots of Mali’s conflict. Moving beyond the 2012 crisis, Clingendael, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Conflict Research Unit (CRU) Report, The Hague (Netherlands).

- China’s Foreign Policy Experiment in South Sudan (July 10th, 2017). Retrieved from International Crisis Group, Report N° 288 / AFRICA, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/south-sudan/288-china-s-foreign-policy-experiment-south-sudan.

- Chivvis, Christopher S. (2016). The French War on al Qa’ida in Africa, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY (USA).

- D’Agostino, Glauco (June 2010), Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre, Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (January 25th, 2014). The Tuareg’s Hope and Great Patience. For Now… Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/tuaregs-hope-great-patience-now/

- de Guttry, Andrea, Sommario, Emanuele and Zhu, Lijiang (2014). China’s and Italy’s Participation in Peacekeeping Operations, Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland (USA).

- Facon, Isabelle (July 2017). Russia’s quest for influence in North Africa and the Middle East. Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Observatoire du monde arabo-musulman et du Sahel.

- French and West African Presidents Launch Sahel Force (July 03, 2017). Retrieved from http://uhuruspirit.org/news/?x=10483#.WjlJudLia70.

- Gazprom International completes exploration in Algeria (April 29th, 2016). Retrieved from http://www.gazprom-international.com/en/news-media/articles/gazprom-international-completes-exploration-algeria.

- Hahn, Julia (May 28th, 2014). Niger sets new terms in uranium ore deal with Areva. Retrieved from Deutsche Welle, http://www.dw.com/en/niger-sets-new-terms-in-uranium-ore-deal-with-areva/a-17667618.

- Herreros, Romain (19/05/2017). Au Mali, Macron veut “accélérer”, “sans barguigner”, contre les jihadistes. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2017/05/19/emmanuel-macron-sur-la-base-militaire-de-gao-au-mali_a_22098936/

- Lebovich, Andrew (July 2017). Bringing the Desert Together: How to Advance Sahel-Maghreb Integration, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), London (UK).

- Massoni, Marco (2016). Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa, in Ministero della Difesa, Centro Militare di Studi Strategici (CeMISS), Osservatorio Strategico, Year XVIII, issue

- Ould – Abdallah, Ahmedou (June 30th, 2017). France G5 Sahel Summit in Bamako. Retrieved from Centre for Strategies and Security for the Sahel Sahara, http://www.centre4s.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=184:france-g5-summit-in-bamako-&catid=39:article.

- Porter, Geoff D. (2015). Questioning Algeria’s Non-Interventionism. Institut Français des Relations Internationales (IFRI), Politique étrangère 3:2015 Focus | Algeria, a New Regional Power?

- Arabia pledges $100 million and UAE $30 million for Sahel anti-terror force (December 13th, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.france24.com/en/20171213-africa-counter-terrorism-sahel-saudi-arabia-pledges-100-million-uae-g5-macron.

- Seybolt, Taylor B. (2007). Humanitarian Military Intervention. The Conditions for Success and Failure. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Solna (Sweden).

- Thomas, Yanis (March 10th, 2015). Les Opérations Sabre et Barkhane en violation de la Constitution. Retrieved from https://survie.org/billets-d-afrique/2015/243-fevrier-2015/article/les-operations-sabre-et-barkhane-4908.

- ‘UN Should Do Its Best to Find Money’ for New Army in Africa – Libyan Politician (05.11.2017). Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/analysis/201711051058836455-libya-migration-crisis-sahel-army/