by Glauco D’Agostino

This is the full version of the article published first in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie“, Year XVII, no. 80 (3 / 2019) “PAKISTAN. A RISING GLOBAL PLAYER IN THE EMERGING GEO-STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2019.

Abstract

Pakistan arose from the Indian Empire ashes first as a British Dominion, later as the independent Islamic Republic, therefore with a constitutive definition marked by religion. There is no doubt Islam is the heart of its identity. The Nation, yet, feeds in its multi-cultural layout and naturally does not exhaust it either in the Islam-Hinduism dialectic or in its religious feature, because of differences within its borders pouring into a manifold of patterns of life, traditions, religious and legal references, cultural events.

Pakistan is the result of indigenous cultures among the oldest in Asia and the world, such as the Indus Valley. The country lay is also a fruit of conquests and migrations that did not prevent from rooting deep unifying behaviours. Here we only point out some salient aspects of the resulting ethnic and stylistic architectural mix, framing them in their time in terms of genesis and development.

Minorities are an integral part of Pakistan’s culture: from the ethnic ones of Saraikis, Siddhis, Aymāq, Hazaras and Dards, to those multi-ethnic like Muhajirs and Gujǎr, from those religious as Christian, Buddhist and Bön, to those ethnic-religious like Hindu, Sikh and Zoroastrian Parsi. These minorities must represent for Pakistan not a problem but an asset, along with the regional autonomies constitutive of the national cultures. Pakistan can overcome the challenge of a well-ordered internal and external coexistence resorting to its roots and the unity of purposes from its components, without giving up its multifaceted cultural structure, as well.

Keywords: Pakistan, Islam, Islamic Republic, Hinduism, Sikh, minorities, regional autonomies, Indian Empire, Mughal architecture, colonial architecture, Islāmābād, Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan, Āzād Jammu and Kashmir.

***

Identitarian core and cultural mix

“You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”[1]

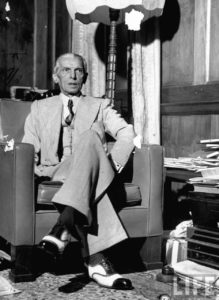

Fig. 2 – Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, Qāʾid-e Aʿẓam, May 1946 (photo from https://www.funyarn.comfounder-of-pakistan-mohammed-ali-jinnah-rare-photos)

These are words of Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, Shiite Muslim from Sindh previously acclaimed “the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unit” after the success of the 1916 Lucknow Pact. He spoke like that in 1947 during his first speech at the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in his capacity as Governor General. Qāʾid-e Aʿẓam (the Great Leader and Father of the Nation) this way reiterated his decades-long battle in favour of religious freedom for all communities.

So, Pakistan arose from the Indian Empire ashes on this basis. Later, it would subject to the splitting of its eastern part (Bangladesh) in 1971, when it had already dropped from its status as a British Dominion in 1956 choosing to establish the Islamic Republic; therefore, a newly formed statehood with a constitutive definition marked by religion. There is no doubt Islam is the heart of its identity, as an evidence of the people faith (96% are Muslim) but also of its tragic recent history that has led to millions of Muslim refugees from India. Yet, those Jinnah’s words remain the gist of its multi-cultural layout, which the Nation still feeds of and naturally does not exhaust either in the Islam-Hinduism dialectic or in its religious feature but takes form in “the might of the brotherhood of the people”[2] and symbolically in “the interpreter of our past, glory of our present, inspiration for our future”, referring to the flag in the national anthem Pāk Sarzamīn (The Sacred Land).

Approach to the issue of Pakistan cultural hallmarks is not an easy exercise precisely because of differences within its borders, starting with the multi-ethnic feature of its 200 million inhabitants pouring into a manifold of patterns of life, traditions, religious and legal references, cultural events. Obviously, looking at its current national boundaries does not mean forgetting those past experiences, although exogenous, that have forged the historical and cultural identity giving birth to the modern nation.

Pakistan, encased between India, Afghanistan, Iran and China, is the result of indigenous cultures among the oldest in Asia and the world, such as the Indus Valley that began in the 4th millennium B.C. The country lay is also a fruit of conquests and migrations attested, for example, by the shalwar kameez, the national dress coming from Turko-Iranian nomadic invaders and consisting of wide trousers and a long tunic. All this did not prevent from rooting deep unifying behaviours such as wasta (a kind of personal connection used to gain something in return for protection and unity) or izzat (the concept of honour);[3] but it also produced an extremely assorted anthropic mosaic where each piece of history meets some of its ethnic groups in their customs and traditions, folklore, language, music, literature, cooking. We shall only point out some salient aspects of the resulting ethnic and stylistic architectural mix, framing them in their time in terms of genesis and development.

Punjab

Punjab, “the land of five rivers” as mentioned in the Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahābhārata,[4] has given its name to the largest ethnic group, the Punjabis in fact, whose identity has formed at the beginning of the 18th century, when the Misls, the “aristocratic republics” of the Sikh Confederacy, began their rise. Punjab hosts over half of Pakistan population, which mostly speak a local language of Indo-Aryan origin, as well as wide spreading Hindi, Urdu and English. In turn, the Punjabi language has two forms of script: Gurmukhī, which Sikhs has been applying since the 16th century, and Shahmukhī, a Perso-Arabic alphabet the Muslims of the region use.[5] The dual form of writing reflects the distribution of religious affiliation: while in West Punjab the vast majority of people is Muslim, in East Punjab Sikhism and Hinduism are better represented. The fact that Gurmukhī is official Punjab’s script finds an explanation in the following connections:

- The historical Sikh presence in the area, first by the already mentioned Misls, then by the Khalsa Raj, which ruled from Lahore for half a century between 1799 and 1849, year of its annexation to the British Empire;

- The Adi Granth (the First Book), the original sacred text of Sikh religion, has been written in Gurmukhī.[6]

In the south, Saraiki (an Indo-Aryan language of the Lahnda branch, that is, of Western Punjabi) is the most widely spoken idiom, as Saraikis (or Multanis), which number as many as 20 million, speak it although the awareness of their distinct ethnic identity developed just in the 1960s. The majority adheres to Islam, though there are Hindu, Christian and Sikh minorities.[7]

The Punjabis stand out for their expansiveness, hospitality and tolerance, so much so that all cultures and traditions are accepted and performed with no exclusions and ostracism. In the capital Lahore, people, who almost all are Muslim, celebrate the ‘urs (death anniversary of a Sufi saint) of Shaykh Syed ʿAlī al-Hujwīrī and Shah Hussain, revered writers of the 11th and 16th centuries respectively;[8] they also welcome the Basant, the Indian spring of Hindu origin, and many cultural festivals, such as the Horse and Cattle Show, which is a performance with historic parades, cattle racings and folk dances and games. Sikhs focus their religious pilgrimages on the eastern and northern Punjab, mainly on Nankana Sahib, the city that gave birth to the founder of Sikhism, Gurū Nānak, as well as on two gurdwārās (worship places): Darbar Sahib of Kartarpur, where he died and his ashes rest; and Panja Sahib of Hasanabdal, where the gurū’s handprint have believed to be. In particular, just complying with the “sacred vision” of Kartarpur gurdwārā, which is close to the Indo-Pakistani border, causes a Sikh turnout on the Indian side.

Punjab, also due to its big size, gathers a good part of the historical records of Pakistan, crossing history from Indus Valley (or Harappan) civilisation up to contemporary time. South-east of Lahore, there is the archaeological site of Harappa, an ancient city that appeared around 2600 B.C. and whose remains emerged in the 1920s. Right in the mid-Bronze Age, the Harappan civilisation developed along the Indus River Valley with identity features of a centralised urban culture, an agricultural and commercial structure, a set of evolved social and economic rules, and a written documentation system.[9] This civilisation had spread from the Himalayan slopes to the Indian Ocean, involving a large area that encompassed parts of present Pakistani and Indian Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan and the Indian Gujǎrāt. In addition to Harappa, the other discovered big city is Mohenjo-Daro, whose remains are in Sindh and reveals the same peculiarities. The Harappan civilisation ended in the mid-2nd millennium B.C., ousted by the Vedic one that affected the area of present-day Pakistan and northern India.

Fig. 8 – Kallar Kahar: Katas Raj Hindu-Shaivite temples, Shiva temple (photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 7 – Kallar Kahar: Katas Raj Hindu-Shaivite temples, the sacred pond (photo by Talhaumar10, 2016)

In the far northern Punjab, also Taxila archaeological site, very close to already mentioned Hasanabdal, reveals artefacts dating back to the Indus Valley civilisation, even though the founding of a big urban settlement date around 1000 B.C. However, it is in the 3rd century B.C., during the Maurya Empire rule, that Taxila played an important role.[10] Following Emperor Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism, the city became a centre of Buddhist teaching: the ancient Buddhist sites that still today are open to worship are of the same period. Among these, the Dharamarajika Stupa, built on Ashoka’s instruction, contains the Buddha’s sacred relics, while the gold and silver coins, gems, jewellery and other antiques found on the ground are now in the Taxila Museum. The stupa is one of the earliest examples of Gandhāra Buddhist Art, which would have more fully flourished between the 1st and 5th centuries A.D. and we will discuss later. As well as the Katas Raj Hindu-Shaivite temples located near Kallar Kahar, northern Punjab, whose building started from the 4th century under the imperial Gupta dynasty, are other examples of religious art. The temples connect each other by walkways and arise around a sacred pond named Katas believed to have been created from Shiva’s teardrops.

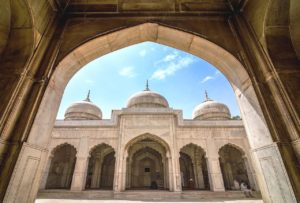

Fig. 9 – Lahore: Royal Fort, Moti Masjid

While each of the foregoing locations links to a single even so noble historical experience, Lahore is a city of thousand contradictions. The millenary city already in 982 had reputations of adorned with “impressive temples, large markets and huge orchards.”[11] Today, it is a huge modern city, which nevertheless, as the heart of various past powers, contains and sums up the dignity of its own history. However, Lahore still fastens to the splendour of the Mughal Empire, of which it was temporary capital at the end of the 16th century and for sure its cultural centre. The city holds many examples of Mughal architecture set with original stylistic qualities from the fusion of Islamic-Persian, Central Asian, and indigenous arts. Among the most prominent are:

- The Shahi Qila (Royal Fort), founded in 1566 by Sindhi Akbar-e Aʿẓam (the Great) in a syncretic architectural style with both Islamic and Hindu motifs, and rebuilt in the 17th century;[12]

- The mausoleums of Emperor Jahangir and his 20th wife Nur Jahan, showing Persian influences from the Safavid style. Both, according to the Punjabi customs, have no domes and are clad in red sandstone and inserts in parchinkari (or pietra dura). The former, built in 1637, has four corner minarets today not present in the latter;[13]

-

The Wazīr Khān Masjid, built in 1634-41, dedicated to the Governor of the time and still deemed as one of the most beautiful mosques of South Asia;

The Wazīr Khān Masjid, built in 1634-41, dedicated to the Governor of the time and still deemed as one of the most beautiful mosques of South Asia; - The Shalimar Gardens complex, created in 1641-42 with intent today we would call ecological, and even at the time meant to achieve the utopia of perfect coexistence between man and nature.[14] Designed according to the Chārbāgh quadripartite drawing of Persian origin, it is coeval (as well as the three previous monuments) to the Tāj Mahal of Āgra and fruit of the initiative of Emperor Shāh Jahān I, the King of the World;

- The Badshahi Masjid (Imperial Mosque), the largest mosque in South Asia after Islāmābād’s Shāh Fayṣal Masjid. It was built in 1671-73 by Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir and today harbours 100,000 faithful (5,000 in the prayer hall and 95,000 in the courtyard and below the arcades). Four minarets and three domes covered in white marble adorn it. The similarities with the Jama Masjid in Delhī, taken as a model by Aurangzeb, are evident since he had been the promoter when he was not Emperor, yet;

- The Mochi Darwaza (Cobbler Gate), surrounded by a bāzār that is renowned for its shops of dried fruit, kites and fireworks.

Fig. 12 – Lahore: Junction Railway Station (photo by Joe mon bkk, 2015)

Lahore is also home to numerous British-colonial buildings of various stylistic forms (Neo-Gothic, Gothic Revival, Indo-Saracenic Revival, Indo-Pak revival), a mix of European and Indo-Islamic components generically unified under the term Indo-European representative style. Between 1858, when the British Raj was born after the Mughal fall, and 1956 marking the end of the Crown Dominion, the British developed a large building and infrastructure renewal program.[15] They focused on new administrative buildings and public facilities, often restoring but sometimes injuring the urban features. Rightly or wrongly, they were bearing the historical legacy of the Delhī capture, when had destroyed a priceless architectural, cultural, artistic, literary and objects heritage.[16]

Undoubtedly, British building policy brought a wind of modernisation, still visible today. Lahore, with its significant architectural projects of that time, is a demonstration. Examples are the urban facilities (the Junction Railway Station, Tollinton Market), the cultural services (the Qāʾid-e Aʿẓam Library, the Government College University, the Aitchison College, the Lahore Museum), the administrative buildings (the Metropolitan Corporation Hall, the General Post Office), the religious services (the Neo-Gothic Anglican Cathedral Church of the Resurrection, the Roman Byzantine-style Belgian Capuchin Cathedral of the Sacred Heart). Among the post-colonial Pakistan buildings, Minar-e-Pakistan and the Grand Jamia Masjid stand out. The former, erected between 1960 and 1968, has been designed by an architect from Dagestan in the place where the Resolution for a separate Muslim homeland was adopted; the latter is a 2014 Mughal-style mosque.

From an architectural point of view, Punjab is not only Lahore, of course. In Multan, the mausoleum of the Sufi saint Shāh Rukn-e-Alam (Pillar of the World) dating back 1320-24 shows a syncretic architectural style with “central Asian and Persian influence, circular or polygonal forms, and extensive use of local material.”[17]

Rawalpindi, very close to the capital of Pakistan Islāmābād to which it ceded the role in 1961, is an ancient city that has kept its historical urban pattern enlivened by bustling artisan markets. Among its architectural highlights, I like to recall those that arose in the 1860-80 colonial decades, when the first headquarters of the famous Murree Brewery corporation, the St. Paul Presbyterian Church and the Railway Station were born. Also, the Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral and the Government Murray College in the prosperous northern city of Sialkot, the Indo-Saracenic-style Ghanta Ghar (Clock Tower) of Faisalabad and the Omar Hayat Mahal of Chiniot are from the colonial era. In particular, the latter, a haveli (traditional mansion) built simply with bricks and mortar between 1923 and 1935, is a woodworking-style jewel, sadly in a poor state of repair. However, its outside shows an uncommon decorative mastery, as its inside flaunts wonderful Jharokas, that is, stone and wood windows leaning out the upper floors.[18]

In Chiniot District, the Aḥmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, an Islamic religious Order whose theology has deemed as a deviation from Islamic orthodoxy (D’Agostino, 2010), based in Chenab Nagar, the new name of the historic Rabwah. The Aḥmadi Masjid-e-Aqṣā lies here. It is the largest mosque of the Community world, erected between 1966 and 1972 at the behest of Mirza Bashir-ud-Dīn Maḥmud Aḥmad, Khalifatul Masih II (namely, the 2nd Caliph of the Community). The stylistic traits, albeit in a modern key, clearly recall the Mughal architecture of the Jahangir Mausoleum and the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, confirming the evocative power of this stylistic typology.

Sindh

Sindh, the southernmost of the Pakistani provinces, is inhabited by Sindhis (the largest ethnic group of origin alternately Baluchi or Pashtun), Muhajirs (immigrants), Punjabis and, to a lesser extent, Pashtuns. Around Karachi, there is also a small community of Zoroastrian Parsis, the result of historical migrations from Persia during the Arab conquest.

Sindhis, like Punjabis, are predominantly Muslim generally influenced by Sufism, with Hindu and Sikh minorities, and speak an ancient local Indo-Aryan language, although those of Baluchi origin verbalise in Saraiki, which we have already seen. They incline towards a rural lifestyle and in the desert region of Tharparkar District are semi-nomad. Women wear very embroidered typical costumes with heavy silver jewellery. Traditions are very perceived, especially in the countryside, and this has generated an art form deemed as the Sindh’s cultural heritage: the Bhagat, which combines songs, dances and drama in an elegant night show led by the main character, the Bhagat, hence the name of the art form. Another cultural event celebrated throughout the province is the Sindhi Cultural Day when common people dress traditional shawls and hats and give life to open-air activities ranging from musical concerts to poetry events, to seminars.[19]

In Sindh, almost one inhabitant out of five is Muhajir, that is an immigrant from India in the national partition process or his descendant. This group, heterogeneous and multi-ethnic but generally Muslim, came from Mumbai, Berar, United Provinces, Hyderabad, Baroda, Kutch and Rājputāna Agency, the latter as a British agency bringing together the various princely states of present-day North-Western India; but another large group, headed to the Pakistani Punjab, came from Indian Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Delhī (IES, 2019). Today, this community of 20 million members has retained some of the Indian atavistic features (such as propensity to business) but it does not usually identify with the ethnicity or region of its roots, preferring to build a more pragmatically surrogate identity within the new forcibly and artificially social aggregate and finding common expression in the Urdu national language.

Fig. 19 – Nagarparkar: Gori Jain Temple (photo from https://swarajyamag.commagazinefaith-under-a-shadow)

From an architectural point of view, also Sindh comes up with a vast proposal of historical heritage, from the remains of the already mentioned Mohenjo-Daro to modern times. Notable examples are the Nagarparkar Temples, consisting of 14 Jain religious architecture but also a mosque borrowing a similar constructive style. Jainism (the Way of Victory), a dharmic religion appeared as early as the 9th century B.C. and whose foundations date back to the 6th century B.C., left many splendid monuments all over India; Nagarparkar’s, now located near the Indian border, are a complex of temples built between the 12th and 15th centuries inspired by the classical Hindu art of Guptas. The 1375-76 Gujǎrāti-style Gori Temple contains Jain frescoes that are the oldest still existing in the northern regions of the Indian sub-continent, and the 52 Islamic-style domes of its ritual pavilion testify the mutual exchange in religious art of the area.[20]

Still in the south, another site documenting Hindu, Persian, Muslim, Mughal and Gujǎrāti influences on southern Sindh’s Chaukhandi style, is the Makli Hill Necropolis near Thatta, among the largest in the world, containing between 500 thousand and one million sepulchres dedicated to rulers, Sufi saints, philosophers and military. The tombs, mostly in finely decorated sandstone, date back in a period between 14th and 18th century (Naqvi, 1973). Thatta, a Sindh Middle Age capital, also enjoys many Mughal-era monuments, including the Jamia Masjid of Shāh Jahān of 1647. The building, which is inspired by many architectural styles (Mughal, Safavid, Timurid), appears like an exhibition of tiles among the most refined in South Asia.

Karachi, the first capital of Pakistan, is a cosmopolitan metropolis on the Arabian Sea that grew from the 400 thousand inhabitants at the time of independence to the current 15-20 million. A hard immigration flow and urbanisation have endangered the social identity of the city but the architectural recognisability of its historic centre, as well. The Jahangir Kothari Parade, a walkway inaugurated in 1920, and Saddar Town (downtown), a concentration of British colonial architecture, have changed their face under the weight of new skyscrapers.[21] But Karachi can still boast a remarkable architectural heritage, albeit in some cases in need of more maintenance:

- Colonial architecture

Fig. 21 – Karachi: Roman Catholic St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Frere Hall, one of the first colonial buildings because erected in 1865, was born as city hall. Its architecture is a prime example of a stylistic fusion of this period, displayed in Venetian-Gothic style with elements of British and local approach.[22] Another example is the Karachi Port Trust Building from 1916, with a curved façade in British, Hindu and Gothic styles and a Roman-style dome. The Gothic Revival also shows up in the nearby Merewether Clock Tower of 1886 and the Roman Catholic St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The latter emerged in 1881 on the same site of Sindh’s first church, born 36 years before. Mohatta Palace, built in 1927 and now a museum, discloses an Indo-Pak revival style and the Rājasthāni roots of its original owner, who wanted pink Jodhpur stone in its beauty;

- Modern architecture

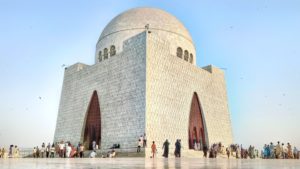

The skyscrapers include the headquarters of Habib Bank Plaza (1963-72), located in the financial hub of Karachi, and those of MCB Bank (2000-05). The Modernist movement inspired the Masjid-e-Tooba (or Gol Masjid), created in 1966-69 in Mid-century style (an International style offshoot) with a big dome of 66 m in diameter, as well as the white-marble Mazar-e-Qāʾid (1970), the final resting place of Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, his sister Mäder-e Millat (Mother of the Nation) Fāṭimah Jinnah, and Liaquat ‘Alī Khān, the first Prime Minister of Pakistan. The Āgā Khān University Hospital, a complex founded in 1985 by Āgā Khān IV Shāh Karīm al-Ḥusaynī, is yet another example of modern buildings recovering combinations of traditional architectural styles, in this case, Indo-Persian and Mughal.

Balochistan

The indigenous people of Balochistan, the Balochis are about 6.8 million and accounted for 3.6% of Pakistan’s population: 50% of them live in Balochistan, 40% in Sindh, others in Punjab. They speak Balochi, a branch of Northwestern Iranian languages, and Urdu, and are mostly Sunni Muslim, although there are Shiite and Mahdavi Zikri minorities. The Zikris, whose name in Urdu derives from the corresponding Islamic invocation practice (dhikr in Arabic), in the Kalima of Shahāda mention the name of the Māhdī instead of Muḥammad as the last Prophet of Allah, but follow the Sunna (D’Agostino, 2010).

The Balochis, many different clans and tribes that are traditionally organised and led by chiefs, are semi-nomadic people, some travelling on a seasonal basis, others living in a home and working in agricultural activities. Their relationship to Pakistan’s dominant ethnic groups is not simple. They bear allegations of a deficient sense of national identity and an atypical lifestyle, no doubt by geographic isolation that led more than 50% of Balochis under the poverty line (IES, 2019). Men’s clothing includes a jamag (a long and wide shirt), a shalwar (inflated trousers), and a pag (a turban). Women wear a pashk, that is a long shift until the ankles, and a shawl covering head, shoulders and upper body; they use elaborate decoration and jewels.

The Siddhis, which form an ethnic group originating from the Bantu peoples of the East African region, also reside in Balochistan and are predominantly Sunni Muslim with Hindu and Roman Catholic minorities.[23] Balochistan, the largest and least densely populated province of Pakistan, shares part of its border with Iran and Afghanistan, from which it has historically absorbed language and customs. Indeed, Aymāq and Hazaras live here, as well, the former mostly Sunni Muslim but the latter Twelver Shiite and Ismaili. Aymāq, who also scatter in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, are nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes speaking a dialect of Eastern Iranian family and living in traditional Afghan black tents. Hazaras, originating from Hazarajat in central Afghanistan, speak a variant of Darī or Farsi and include Sunni minorities. But there are also Aymāq Hazaras, a combination of the two ethnic groups, who are Sunni Muslim semi-nomadic people living (unlike the Aymāq) in Mongol-style felt-covered yurts.[24]

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is an actual example of land-sharing by people with different customs and traditions that often Pakistan recognises as rules coexisting in their areas alongside the State laws. Pashtuns (or Paṭhāns) are the largest ethnic group and share many features with neighbouring Afghans. They speak Pashto (or Paṭhānī), an Eastern Iranian language, but Urdu as the official Pakistani language also is widespread at the grassroots level, as well. They stand out for a deeply religious nature, tribal and collectivist organisation, high adaptability to geographic and climatic harshness. Another distinctive feature of their style is that they refer to ethical and work values and free hospitality granted beyond the ethnic and religious differences (IES, 2019).

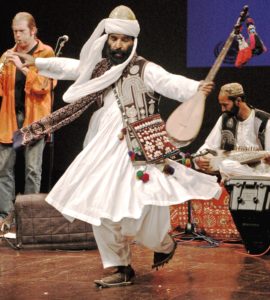

Pashtun garments are lavish and colourful, as the Khattak Paṭhāns’ annual dance performances in the Peshawar stadium testify. Their menswear, in the likeness of the Baloch clothing, consists of a khət paṛtūg (in Urdu, shalwar kameez) with a pakul, the Pashtun hat. Tribal chiefs sometimes wear a qaraqul, a triangular hat of Central Asian origin. In Peshawar, young men usually wear a wide kufi, that is a brimless, short, and rounded cap, and in Kandahar a circular or cylindrical topi hat. Women wear long traditional dresses adorned with handmade jewellery, along with cowls or kerchiefs on their heads, and in the Kaghan Valley they use captivating handmade clothes.

A myriad of ethnic groups also lives in this province. Many of them form several sub-groups of the ethnic Dard family, generally united by a shared language of Indo-Aryan origin, with variations in local ethnic idioms. The majority religious faith is Islam (in its Sunni, Shiite and Nurbakhshi Sufi versions) but there are also Hindu and Buddhist minorities. Among the most engaging sub-groups are:

- The Kaĺaśa (Waigali or Wai), indigenous Asiatic people whose ancestors migrating to Afghanistan and then to the Chitral District of this province. Deemed as the smallest and most peculiar ethnic-religious group in all Pakistan, they wear black and profess a form of animism or ancient Hinduism;[25]

- The Kohistanis, Muslim since the 15th century, speak Indus Kohistani or Pashto. They have semi-sedentary habits, living in homes close to agricultural fields in wintertime and mountain camping in the summertime.

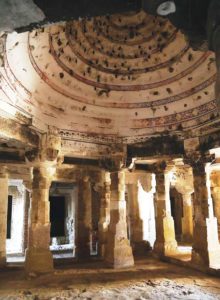

The province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa includes the famous Khyber Pass, the access route many conquerors used in the past; but above all it hugs the historical region of Gandhāra (the land of fragrance), corresponding to an ancient state that had been existing for two thousand years from the 15th century B.C. to the 6th century A.D. It is here the Gandhāra civilisation developed, and it is this region that became the cradle of Buddhism and its art later extended to the Far East. Starting with the establishment of the Hellenistic Indo-Greek Kingdom and Persian art influence, Gandhāra civilisation gave life to the Greco-Buddhist style. Witnesses from 2nd century B.C. remains in the Butkara Stupa of Mīngawara containing Buddha’s original relics. This stupa locates in the Swat Valley, which has become a pilgrimage land to approximately 400 sites of the area containing thousands of stupas and monasteries; this is because the Buddhist memory hands down that the Buddha himself, in his Siddhārtha Gautama’s reincarnation, preached to local people.[26]

From the 1st to the 5th century A.D., the Buddhist architecture reached its peak in what is called Gandhāra Art, exactly. In Mardān, in the Peshawar Valley, there are ruins of the Takht-i-Bahi (Throne of the water spring) Monastery and Neighbouring City at Sahr-i-Bahlol, an Indo-Parthian archaeological site. The 1st century A.D. Takht-i-Bahi, today one of the Buddhist holy places, hosts a row of colossal Buddhas in a courtyard of the main stupa.[27] For this reason, in the 5th century, the Gandhāra region was a pilgrimage destination of the Chinese Buddhist monk Fǎxiǎn, who for 15 years had been following the Buddha’s footsteps in the Peshawar and Swat Valleys, visiting many sacred Buddhist sites (Naqvi, 1973).

The current provincial capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is Peshawar, the northernmost city in Pakistan that in the 2nd century A.D. held with the name of Puruṣapura the position of capital of the Kushan Empire, when it extended from Bukhara to Pamir, to Central India.[28] The city boasts mythical origins (according to traditions, Ahura Mazdā, the Supreme God of Zoroastrianism, created it) and it was reputed the crown jewel of Bactria.

Gilgit-Baltistan and Āzād Jammu and Kashmir

The province of Gilgit-Baltistan and the autonomous territory of Āzād (Free, in Urdu) Jammu and Kashmir connect here due to the affinities binding them to the broader historical-cultural region of Kashmir. A very unique ethnic and religious melting pot warms this area.

In Gilgit-Baltistan, the prevailing ethnicity is the Balti’s, a Tibetan offspring with Dardic admixture present also in the cities of Lahore, Karachi, Islāmābād and Rawalpindi. Their language is from the Sino-Tibetan family, and most of them profess the Shiite Islam with Sunni or Nurbakhshi Sufi Muslim minorities and other allogeneic groups belonging to Tibetan Buddhism or animist-shamanist Bön religion. Shiite Muslims, but of Nizari Ismaili worship, are present in the Gilgit’s Hunza region, as well as in the Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. They are part of the following groups:

- The Wakhis (or Khiks), who speak a language of the Iranian family;

- The Burusho (or Botraj), also settled in the Gilgit’s Nagar Valley and verbalising in Burushaski (which is an isolated language) or in Khowar.

Gujǎr, a large heterogeneous group that differentiates internally in terms of culture, religion, occupation, and socio-economic status, live especially in all the above provinces but also in Sindh.

The Kashmiris of the Āzād Jammu and Kashmir, originating from the India-administered Kashmir Valley and similar in customs to the Jammu region, also belong to the already described ethnic family of Dards. In addition to their Kashmiri language, they use Hindustani (a Hindi-Urdu combination) and are predominantly Muslim with Hindu and Sikh minorities. Their history links closely to the events of the 1947 partition of British India, as the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, whose population at the time was Muslim at a rate of 77%, had the opportunity to join the newborn British Dominion of Pakistan. The local Mahārāja, a Hindu believer, favoured the intervention of the Indian army, which thus took possession of the territory. Under the UN auspices, the parties reached a provisional agreement whereby a small part of the former Princely State remained under Pakistani administration, while most assigned to the administration of the Delhī government, causing an exodus towards the free area, the one called Āzād.[29]

A story related to the same events is that of the Princely States of Hunza (or Kanjut) and Nagar. At the time, both chose to join Pakistan, even though India disputed this decision and still now claims its sovereignty. After 1947, the federal government of Pakistan recognised the two Princely States as autonomous subjects until 1974, when it dissolved them then giving rise first to the Northern Areas and later to the province of Gilgit-Baltistan.

The north-eastern areas of Pakistan scatter with old fortresses and towers. In the extreme northern part of Pakistan bordering the Afghan Wakhan Corridor and the Xīnjiāng Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, Baltit Fort lies close to Karimabad, a town in the Gilgit’s Hunza Valley. Baltit Fort, a 17th-century Balti-style building on the same site of earlier historical strongholds, boasts a design similar to Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital. Baltit is the original name of the city, which was renamed Karimabad in honour of the Āgā Khān IV Shāh Karīm, 49th Nizari Imām of the Khojas Ismaili community. His Aga Khan Trust for Culture, an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, has renovated the Fort building in the 1990s.

To understand the nature of the customs in Baltistan, one must go to the Skardu Valley, known as Tibet Khurd (the Little Tibet) since the Mughal era because of people lifestyle similar to Tibet’s. Yabgo Khar (the fort on the roof) is an old fort and palace located in Khaplu, east of Skardu town and along the road leading to Ladakh, a region in the India-administered Jammu and Kashmir. The architecture of the fort, built in 1840, shows up Tibetan, Kashmiri, Ladakhi, Balti, and Central Asian stylistic influences, enhancing the multi-cultural features that meet its geographical position and the ethnic mix coming from history. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture recently restored even Yabgo Khar.[30] Among its most attractive architecture pieces, Khaplu includes some buildings inspired by the style used in the Kashmir Valley: for example, the Chaqchan Mosque (the Miraculous Mosque) adhering to the Sufi Order of Nurbakhshiyya, a Kubrāwiyya-offshoot that emphasises unity in the Islamic Umma. Its fabric has been displaying a wattle and daub technique since 1370 when people converted in mass from Buddhism to Islam and built it.[31]

Islāmābād Capital Territory

“The City of the Future”, this way Greek urban planner Konstantinos Doxiadis, the father of ekistics, called it in 1959 as he conceived the new capital project upon urge of Field Marshal Moḥammad Ayyūb Khān, who had recently gained the responsibility of Pakistan’s President. The city, which significantly took the name of Islāmābād in homage to the unifying element of the nation, officially assumed its role as capital in 1961 and the actual one five years later. In developing its master plan, Doxiadis applied the idea of the fan-shaped dynapolis, a modern city in aesthetics and functioning, with a linear diffusion system generated by a central pole. The construction of buildings gave priority to governmental and administrative functions. All the other constituent elements of an ordered and rationally-planned city followed, with residential neighbourhoods, shopping areas, green belts, large arteries and transport hubs, all urban components subjected to strict zoning control.[32]

Not everyone agrees on the government’s decision to entrust the major building interventions to architects and companies from abroad. Some evaluations put that the attempt to mediate between modernity and traditional stylistic features as perceived by external sensitivities gave birth to hybrid architectures with no identity (Alvi, 2009).

Edward Durell Stone, who designed the Aiwan-e-Sadr (the Presidential Palace), the Majlis-e-Shūrā building (the Parliament House) and the Cabinet block of the Pakistan Secretariat, all in a horizontal-style, tried to follow a Mughal approach. But Turkish architect Vedat Ali Dalokay deliberately designed the Shāh Fayṣal Grand Mosque in an abstract-inspired contemporary Islamic style. And Japanese architect Kenzō Tange relied on a modernist formalism-style for the Adālat-e-Uzma Pākistān building (the Supreme Court of Pakistan). In particular, the Grand Mosque, by now a symbol of the city and the nation as a whole, breaks tradition and introduces innovations in architectural language and new aesthetics: it avoids the classic dome, calls forth an Arab desert tent and shows up Turkish-fashioned minarets.

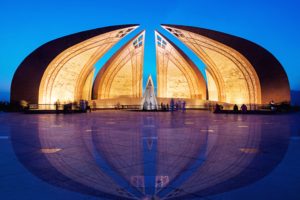

Finally, among the latest buildings to embellish a multi-faceted city, the Pakistan Monument inaugurated only 12 years ago is dedicated to national unity. Its architecture by Pakistani Arif Masoud is perhaps the brightest artistic synthesis of the Pakistani sentiment, a compendium of its historical awareness projected to the contemporary world. The style is once again marked by gently Mughal art. The outlines of the petal-shaped granite structure evoke the muqarnas, that is the vaults with stalactites overlapping and ever more prominent, that decorate, for example, the Imām Mosque in Eşfahān. The four larger petals symbolise the constitutive cultures of the nation: the Punjabi, the Sindhi, the Balochi, and the Pashtun; the smaller ones dedicated to minorities, Āzād Jammu and Kashmir and the Tribal Areas.[33]

Final remarks

Pakistan Monument seems to be the point of reference for understanding the meaning of Pakistan’s presence in the south-central Asian scene. Here the role of Islam as a founding element and unifying heart of national identity did not stand out enough. Of course, Islam is the decisive reason of its cultural and artistic structure not only by recent times (its foundation as Islamic Republic) but starting from 711 when Moḥammed bin Qāsim conquered Sindh, Balochistan and part of Punjab, extending the status of Ahl al-Kitāb (the People of the Book) to Hindus and Buddhists rooted in the area. And then, gradually lasting in a crescendo, with the Ghaznavid, Ghurid, Dehlī Sultanates until the Mughal splendour.

However, as we have seen, minorities (one of the smaller petals of the Pakistan Monument) are an integral part of its culture: from the ethnic ones of Saraikis, Siddhis, Aymāq, Hazaras and Dards, to those multi-ethnic like Muhajirs and Gujǎr, from those religious as Christian, Buddhist and Bön, to those ethnic-religious like Hindu, Sikh and Zoroastrian Parsi. These minorities must represent for Pakistan not a problem but an asset recognised in the terms outlined here, along with the regional autonomies constitutive of the national cultures (the four larger petals). In this sense, the question of Tribal Areas (another Monument petal) remains, in my opinion, controversial since the regional semi-autonomy they enjoyed expired in 2018 with their complete absorption in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Finally, the situation in the Greater Kashmir, not defined on a formal international level: the issue of former Princely States access to either Pakistan or India is a historical still open cut, not so much for their administrative rule (now practically accepted by parties) but in terms of people feeling since they perceive the lost land as an injury to their national identity.

As things stand, Pakistan can overcome the challenge of a well-ordered internal and external coexistence resorting to its roots and the unity of purposes from its components, without giving up its multifaceted cultural structure, as well. Once again citing Jinnah’s words (Jillani, 2013): “We should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community, because even as regards Muslims you have Pathans, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on, and among the Hindus you have Brahmins, Vaishnavas, Khatris, also Bengalis, Madrasis and so on, will vanish.”

***

[1] Shahzeb Jillani (11 September 2013). The search for Jinnah’s vision of Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-24034873.

[2] Douglas M. Rife (1998). The Song of a Nation: The Star Spangled Banner and Other National Anthems. Dayton, Ohio: Lorenz.

[3] IES (2019). The Cultural Atlas. Retrieved from: https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au.

[4] Sir Henry Yule, Arthur Coke Burnell (1903). Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological, historical, geographical and discursive. New ed. by William Crooke, London: J. Murray.

[5] Danesh Jain, George Cardona (July 26th, 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. New York, NY: Routledge.

[6] Encyclopædia Britannica (July 17th, 2017). Adi Granth: Sikh Sacred Scripture. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Adi-Granth-Sikh-sacred-scripture.

[7] James B. Minahan (August 30th, 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

[8] Syed Kumail Hasan (April 04, 2016). Mela Chiraghan – Where the light is stronger than the darkness in Lahore. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1248883/mela-chiraghan-where-the-light-is-stronger-than-the-darkness-in-lahore.

[9] Library of Congress Country Studies (March 08, 2017). Pakistan – Early Civilizations of Pakistan. Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/early-civilizations-of-pakistan-119177.

[10] Embassy of Pakistan in Denmark (n.d.). Pakistan the Craddle of the Oldest Civilization. Retrieved from http://www.pakistanembassy.dk/oldcivilization.html.

[11] V. Minorsky (1937). Hudud al-‘Alam, The Regions of the World. A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D. (translation). London: Oxford UP.

[12] UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d.). Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/171/

[13] James L. Wescoat jr., Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn (1996). Mughal Gardens: Sources, Places, Representations, and Prospects. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

[14] Abdul Rehman (2009). Changing Concepts of Garden Design in Lahore from Mughal to Contemporary Times. Garden History, 37(2), 205-217. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27821596.

[15] Pervaiz Munir Alvi (February 2nd, 2009). Architecture in Pakistan: A Historical Overview. Retrieved from https://pakistaniat.com/2009/02/02/pakistan-architecture-history/

[16] Glauco D’Agostino (2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries). Rome, Italy: Gangemi, p. 185.

[17] Syed A. Naqvi (December 1973). Pakistan: 5,000 Years of Art & Culture, in UNESCO Courier. Paris: UNESCO, pp. 4-6.

[18] Ali Aown (December 03, 2015). Umar Hayat Mahal: Chiniot’s dying ‘wonder’. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/print/1221723.

[19] APP (December 4th, 2016). Sindhi Culture Day celebrated in Sindh. Retrieved from The International News, https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/169748-Sindhi-Culture-Day-celebrated-in-Sindh.

[20] Ema Anis (July 30th, 2016). Secrets of Thar: A Jain temple, a mosque and a ‘magical’ well. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1238823.

[21] Syed Raza Hassan (March 2nd, 2018). Pakistan’s crumbling architectural heritage. Retrieved from https://widerimage.reuters.com/story/from-raj-to-architectural-riches.

[22] Sadeem Shaikh (October 29th, 2015). Frere Hall, a Hundred and Fifty Years Later. Retrieved from https://www.youlinmagazine.com/story/architecture-of-frere-hall-karachi/NDY2.

[23] Zaffar Abbas (13 March 2002). Pakistan’s Sidi keep heritage alive. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1869876.stm.

[24] Muhammad Owtadoiajam (1976). A Sociological Study of the Hazara Tribe in Baluchistan: An Analysis of Socio-Cultural Change. Retrieved from http://www.tribalanalysiscenter.com.

[25] Richard F. Strand (17 May 2011). The kalaṣa of kalaṣüm. Retrieved from http://www.nuristan.info/Nuristani/Kalasha/kalasha.html.

[26] Embassy of Pakistan in Denmark (n.d.). Pakistan the Craddle of the Oldest Civilization, cit.

[27] UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d.). Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/140/

[28] Rafi-us Samad (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. New York: Algora Publishing.

[29] Glauco D’Agostino (December 3rd, 2016). Wounds Still Open in the Indian Area on the Eve of 70th Independencies Anniversary. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/wounds-still-open-in-the-indian-area-on-the-eve-of-70th-independencies-anniversary/

[30] Khaplu Palace wins international award (December 11th, 2012). Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/770456/khaplu-palace-wins-international-award.

[31] Nisar Ali (May 2nd, 2017). Ghanche: One of the most beautiful and culturally rich valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan. Retrieved from https://pamirtimes.net/2017/05/02/ghanche-one-of-the-most-beautiful-and-culturally-rich-valleys-of-gilgit-baltistan/

[32] Hammad Husain (n.d.). Pakistan: Evolving Expressions of Diversity in Architecture. Retrieved from https://www.youlinmagazine.com/story/pakistan-evolving-expressions-of-diversity-in-architecture/NTI=

[33] Pakistan Monument: a source of attraction for visitors (November 03, 2014). Retrieved from https://nation.com.pk/03-Nov-2014/pakistan-monument-a-source-of-attraction-for-visitors.

REFERENCES

- Abbas, Zaffar (13 March 2002). Pakistan’s Sidi keep heritage alive. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1869876.stm.

- Ali, Nisar (May 2nd, 2017). Ghanche: One of the most beautiful and culturally rich valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan. Retrieved from https://pamirtimes.net/2017/05/02/ghanche-one-of-the-most-beautiful-and-culturally-rich-valleys-of-gilgit-baltistan/

- Alvi, Pervaiz Munir (February 2nd, 2009). Architecture in Pakistan: A Historical Overview. Retrieved from https://pakistaniat.com/2009/02/02/pakistan-architecture-history/

- Anis, Ema (July 30th, 2016). Secrets of Thar: A Jain temple, a mosque and a ‘magical’ well. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1238823.

- Aown, Ali (December 03, 2015). Umar Hayat Mahal: Chiniot’s dying ‘wonder’. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/print/1221723.

- APP (December 4th, 2016). Sindhi Culture Day celebrated in Sindh. Retrieved from The International News, https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/169748-Sindhi-Culture-Day-celebrated-in-Sindh.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries). Rome, Italy: Gangemi.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (December 3rd, 2016). Wounds Still Open in the Indian Area on the Eve of 70th Independencies Anniversary. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/wounds-still-open-in-the-indian-area-on-the-eve-of-70th-independencies-anniversary/

- Embassy of Pakistan in Denmark (n.d.). Pakistan the Craddle of the Oldest Civilization. Retrieved from http://www.pakistanembassy.dk/oldcivilization.html.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (July 17th, 2017). Adi Granth: Sikh Sacred Scripture. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Adi-Granth-Sikh-sacred-scripture.

- Hasan, Syed Kumail (April 04, 2016). Mela Chiraghan – Where the light is stronger than the darkness in Lahore. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1248883/mela-chiraghan-where-the-light-is-stronger-than-the-darkness-in-lahore.

- Hassan, Syed Raza (March 2nd, 2018). Pakistan’s crumbling architectural heritage. Retrieved from https://widerimage.reuters.com/story/from-raj-to-architectural-riches.

- Husain, Hammad (n.d.). Pakistan: Evolving Expressions of Diversity in Architecture. Retrieved from https://www.youlinmagazine.com/story/pakistan-evolving-expressions-of-diversity-in-architecture/NTI=

- IES (2019). The Cultural Atlas. Retrieved from: https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au.

- Jain, Danesh, Cardona, George (July 26th, 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jillani, Shahzeb (11 September 2013). The search for Jinnah’s vision of Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-24034873.

- Khaplu Palace wins international award (December 11th, 2012). Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/770456/khaplu-palace-wins-international-award.

- Library of Congress Country Studies (March 08, 2017). Pakistan – Early Civilizations of Pakistan. Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/early-civilizations-of-pakistan-119177.

- Minahan, James B. (August 30th, 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- Minorsky, V. (1937). Hudud al-‘Alam, The Regions of the World. A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D. (translation). London: Oxford UP.

- Naqvi, Syed (December 1973). Pakistan: 5,000 Years of Art & Culture, in UNESCO Courier. Paris: UNESCO.

- Owtadoiajam, Muhammad (1976). A Sociological Study of the Hazara Tribe in Baluchistan: An Analysis of Socio-Cultural Change. Retrieved from http://www.tribalanalysiscenter.com.

- Pakistan Monument: a source of attraction for visitors (November 03, 2014). Retrieved from https://nation.com.pk/03-Nov-2014/pakistan-monument-a-source-of-attraction-for-visitors.

- Rehman, Abdul (2009). Changing Concepts of Garden Design in Lahore from Mughal to Contemporary Times. Garden History, 37(2), 205-217. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27821596.

- Rife, Douglas M. (1998). The Song of a Nation: The Star Spangled Banner and Other National Anthems. Dayton, Ohio: Lorenz.

- Samad, Rafi-us (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. New York: Algora Publishing.

- Shaikh, Sadeem (October 29th, 2015). Frere Hall, a Hundred and Fifty Years Later. Retrieved from https://www.youlinmagazine.com/story/architecture-of-frere-hall-karachi/NDY2.

- Strand, Richard F. (17 May 2011). The kalaṣa of kalaṣüm. Retrieved from http://www.nuristan.info/Nuristani/Kalasha/kalasha.html.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d.). Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/140/

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d.). Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/171/

- Wescoat, James L. jr., Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (1996). Mughal Gardens: Sources, Places, Representations, and Prospects. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Yule, Sir Henry, Burnell, Arthur Coke (1903). Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological, historical, geographical and discursive. New ed. by William Crooke, London: J. Murray.