by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie”, Anul XVII, nr. 78-79 (2 / 2019) “MAREA NEAGRĂ – STRATEGII 2020“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2019.

Abstract

The issue presented here is a reflection on the complexity of communities living together on the same territory, their origins still defining identity and the political determinants that have affected decisions and behaviours of entire social components. The multi-ethnicity, the poly-linguism and multi-religiosity of the people settled around the Black Sea have historically created reasons for interconnections and, alternatively, of rivalry, invasions and looting.

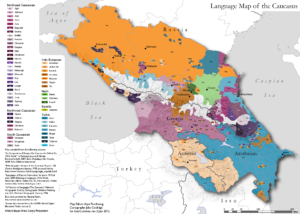

The nation-states on the Black Sea host various ethnic-linguistic and religious minorities that often testify to the reasons for a presence consolidated in history by traditions and behaviours. Some of the most interesting minority groups are those belonging to the following ethnic families: Slavs, Caucasians, Turkic peoples, Pontic Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Romance peoples, Indo-Aryans, Germans. Areas of geo-anthropic relevance can broadly trace because the Christian-Orthodox Slavic communities prevail in the northern and western portions, the Caucasians of various religions in the East and the Muslim Turkic in the South.

If we accept the perspective of historical continuity and the independence status of any country, the Kievan Rus’, the first nucleus of Greater Russia, was born in 882 and developed later to the Russian Empire, the USSR and the present Russian Federation; current Romania and Bulgaria formally born in 1881 and 1908; Turkey in 1923 from the dissolution of the Ottoman Sultanate; but USSR-arisen Transdnestrija, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia and Abkhazija have less than 30 years of life as independent states.

The falls of the Russian and Ottoman Empires, undermined by the rise of nation-states, have undoubtedly weakened the nature of coexistence in diversity, exacerbating ethnic and religious conflicts within communities. Social exclusions multiplied due to interest in determining homogeneity within an often fictitiously unitary framework. It is the season of nationalisms that lasts to the present and is a geopolitical concern. The problem is on managing minorities and their claims in terms of existing or presumed rights. No one minimises national affiliation. Even though, it seems clear that a more suitable instrument for understanding social interactions among groups with different customs and traditions is the examination of ethnic-linguistic and religious ties in their historical context and their relationships with the political power at each time.

Keywords: Black Sea, ethnic identities, multi-ethnicity, poly-linguism, multi-religiosity, Slavs, Caucasians, Turkic peoples, Pontic Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Romance peoples, Indo-Aryans, Germans, nationalism.

***

The imperfection of the current nation-states

The area gravitating around the Black Sea has always been a geo-anthropic ensemble to be interpreted as a unit under its aggregating features and beyond the often cruel political events that have shaped its social life over the centuries. This is because the power of communications among its coasts has articulated the relationships amid ethnic-linguistic and religious groups of the most diversified nature and yet strongly interrelated due to a common interest in managing a space defined in collective terms. The result is a heterogeneous mix of peoples and cultures marked by the phenomenon of continuous migration and contamination of traditions and knowledge.

The falls of the Russian and Ottoman Empires, undermined by the rise of nation-states, undoubtedly weakened the nature of coexistence in diversity and exacerbated ethnic and religious conflicts within communities forced into the national identity straitjacket. It often resulted in ideological constructions damaging minorities, who feel like foreigners at home. Following the lack of an overarching political umbrella governing (or even imposing) cohesion among different ethnic, religious and cultural subjects, social exclusions multiplied due to interest in determining homogeneity within an often fictitiously unitary framework. It is the season of nationalisms that lasts to the present and is a geopolitical concern, running through clash among blocks of alliances, territorial conquests and induction of political and commercial influences.

If this is the backdrop of the stage, the essence of historical acting lies in the peoples’ relationships with their diversity that can hardly appropriately result in assimilation to the dominant culture or even in the assumption of one people-one state. Leaving aside the debate on the phenomena evolution and their possible solutions (which certainly implies historical timings beyond the present contingencies), the issue presented here is a reflection on the complexity of communities living together on the same territory, their origins still defining identity and the political determinants that have affected decisions and behaviours of entire social components.

Fig. 3 – Bucharest (Romania), Patriarchal Orthodox Cathedral of SS. Constantine and Helena, and Palace of the Patriarchate (by the author)

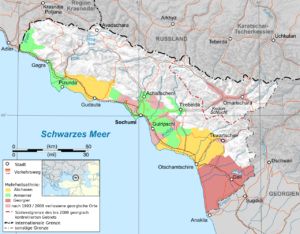

The states formed in the last century and a half that have an outlet on the Black Sea meet the dominant ethnic groups settled on its shores. Russians, Ukrainians and Bulgarians are Slavs and mainly Eastern Orthodox Christians; Georgians and Romanians are ethnic groups in their own right adherents to the prior religion; Turks represent the original ethnic group of the myriad of ethnicities classified as Turkic peoples, all of them Muslims. The newly independent states that appeared in the last twenty years on the Black Sea shores (or inner areas of geographical scope) are Russian-hint secessionist entities, but while Transdnestrija and the self-proclaimed Republics of Donbass are populated by Orthodox Slavs, Abkhazija inhabits Northwest Caucasian peoples, i.e. Georgians and Armenians predominantly Christian either Muslim after the community they belong to.

However, the situation is not so clearly definite, because the nation-states host various ethnic-linguistic and religious minorities that often testify to the reasons for a presence consolidated in history by traditions and behaviours. Some of the most interesting minority groups established around the Black Sea are those belonging to the following ethnic families: Slavs, Caucasians, Turkic peoples, Pontic Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Romance peoples, Indo-Aryans, Germans. Obviously, an ethnic group that forms a majority in a country can be a minority in another area precisely because of migrations, either voluntary or imposed by the political situation. And yet, further investigating, an ethnic group can be a significant minority in a country but is not relevant in an area of coastal scope (see for example the Hungarians in Romania). And this is even more apparent for large nation-states such as Russia and Turkey, where the Eastern Caucasian peoples or the Kurds, the majority in large parts of those countries, do not have a significant presence in the areas gravitating around the Black Sea. Areas of geo-anthropic relevance can broadly trace because the Christian-Orthodox Slavic communities prevail in the northern and western portions, the Caucasians of various religions in the East and the Muslim Turkic in the South.

Let’s try to outline some features of the above ethnic families.

Slavic minorities

The main Slavic minorities in the area (obviously outside their national landmark states) are Russians, Ukrainians and Bulgarians, all settled in areas with mainly Christian-Orthodox people. The Russians are massively present in the Ukrainian Donbass but also in Moldavia, Transdnestrija and Georgia. The Lipovans, a Russian-stream people dissident of the Russian Orthodox Church, are settling since the 18th century in the Budzhak region (namely the Southern Bessarabia currently part of Ukraine), in the adjacent Romanian and Bulgarian Dobruja and in the Bulgarian province of Varna: they belong to the faction of the Old Believers, that is those Orthodox Christians following the traditional rituality before the 1652-66 Reform.

According to the 2014 census, Ukrainians are a minority in Crimea (15.7%) after Russians (67.9%). In that year Crimea was annexed to the Russian Federation, giving birth to the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol’ as two of the 85 entities composing the Federation. Bulgarians, instead, are one of the main minorities in the Ukrainian region of the Black Sea, especially Odessa oblast’ which homes about 150 thousand of them. Ukrainian and Bulgarian communities are present in Moldavia, Transdnestrija and Romania for a total of 600-750 thousand people.

Caucasian minorities

The Caucasian peoples living in areas overlooking the Black Sea can classify into two ethnic families, who are the Northwest and the South Caucasians. Among the former, there are Circassians, Abazins and Abkhaz, who are bound by languages with the same origin; among the latter, Georgians, Lazi and Mingrelians, who are linked by Kartvelian languages closely related to the Abkhaz language [fig. 4]. Thus, Abkhazija [fig. 5] becomes the link between the north and the south Caucasus, with its linguistic, ethnic and religious complexity, which also explains its recent and past historical events. But first things first.

The Circassians in a broad sense (therefore not only Karačaj-Circassia inhabitants) live mainly in Kabardino-Balkaria, Adygea and also Karačaj-Circassia. These three Republics of the Russian Federation welcome about 650 thousand Circassians, who are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Ḥanafī theological school of law. They are the majority of the population just in the first of these republics (57.2% at the 2010 census) but in their local version of Kabardians. In Karačaj-Circassia, however, the dominant ethnic group is that of the Karačajs, who are Turkic people and speak a Qıpçaq Turkic language, although they are Sunni Muslims, too. A smaller ethnic group, the Abazins, originally inhabited western Abkhazija and migrated to the north of present Karačaj-Circassia in the 14th and 15th centuries. Their ethnic and religious features are similar to those of Circassians, and today a small rate of their components lives also in the neighbouring Stavropol’ Kraj. The Abkhaz, in addition to 120 thousand living in Abkhazija, are allocated even in small local communities of Georgia and Ukraine.

The Circassians in a broad sense (therefore not only Karačaj-Circassia inhabitants) live mainly in Kabardino-Balkaria, Adygea and also Karačaj-Circassia. These three Republics of the Russian Federation welcome about 650 thousand Circassians, who are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Ḥanafī theological school of law. They are the majority of the population just in the first of these republics (57.2% at the 2010 census) but in their local version of Kabardians. In Karačaj-Circassia, however, the dominant ethnic group is that of the Karačajs, who are Turkic people and speak a Qıpçaq Turkic language, although they are Sunni Muslims, too. A smaller ethnic group, the Abazins, originally inhabited western Abkhazija and migrated to the north of present Karačaj-Circassia in the 14th and 15th centuries. Their ethnic and religious features are similar to those of Circassians, and today a small rate of their components lives also in the neighbouring Stavropol’ Kraj. The Abkhaz, in addition to 120 thousand living in Abkhazija, are allocated even in small local communities of Georgia and Ukraine.

In Georgia, an overtly Christian Orthodox country perceiving religion as the basis of identity, more than 80% of people are Georgians, but in its Autonomous Republic of Adjara, 30% of the local population (which is still Georgian in ethnicity and language) has traditionally been Sunni Muslim since the 16th century. The religious minority status is not easy for Adjara Muslims (as well as for Azerbaijani and Chechen minorities from inland) due to the historical inheritance of the resistance Georgians opposed in the past to the Muslim Ottoman and Persian Empires; so they are asked a continuous test of fidelity to the state. This often involves public expectations they reject Islamic obligations and traditional customs. Men refraining from drinking alcohol or women wearing a hijāb in public bring loss of social consensus and problems at work, leading to conversion to Christianity, which is majoritarian and, in the people’s perception, helps to conquer a higher social position.[1] However, in Adjara, Muslim organisations are growing due to the help provided by Turkey, which looks to the region for developing good economic relations with Georgia.[2]

Subgroups of Georgian ethnicity are Svans, Mingrelians and Meskhetians, who speak dialects of Kartvelian language group similar to Georgian. The first ones, established in the historical region of Svaneti, in north-west Georgia, are Christian-Orthodox, as well as 400 thousand Mingrelians from the bordering regions of Mingrelia and Abkhazija; the Meskhetians, 77 thousand people located in the southwestern region of Samtskhe-Javakheti, are shared between Christian-Orthodox and Roman Catholic communities. Substantial Meskhetian minorities also exist in the north-eastern Turkish province of Ardahan and along the Georgian borders with Turkey, although in this case, they are Muslims and ethnically and linguistically Turkish.

The very question of Georgian Meskhetian Turks repatriation is still a major political problem for the institutions. The issue arose when, in November 1944, Stalin began the deportation of 120,000 members of this ethnic group from southern Georgia to Central Asia. In the 1980s Meskhetian Turks began their slow still illegal return to their homeland, as there was no law providing for their repatriation. Only in 1999, when the Council of Europe admitted Georgia, the authorities pledged to enact a measure to that effect, implemented in July 2007 with the Law on the Repatriation of Deported People. Even now, 12 years after the approval of this law, many Meskhetian Turks still do not have recognised the status of repatriated and have to give up the rights to health and economic assistance, in addition to the claims concerning the right of ownership on property abandoned at that time or on those acquired in more recent times.[3]

This question makes clear the historical links between Georgia and Turkey, ties we can still read through the connections between ethnic-religious minorities and places, in a territorial continuity going beyond the current borders. While Meskhetian Turks are, if you will, a bit of Turkey in Georgia, the Lazi [fig. 10] witness a piece of Georgia in Turkey. This subgroup of Georgian ethnicity speaks the Lazuri language of Kartvelian origin but professes Sunni Islam from the 15th century. There are two different groups of Lazi, the first allocated in the eastern Black Sea region (Rize and Artvin provinces) and the other in the west (Adapazarı, Sapanca, Yalova and Bursa provinces). The last-mentioned are heirs to immigrants escaping Ottoman-Russian war in the late 19th century; in the latest 20 years, they have mostly migrated to the main cities of western Turkey.[4] One of the most pressing demands of Laz minority has been increasingly focused on the right to education in Lazuri language, which UNESCO classed as endangered; only in 2013 a new government policy of “democratisation” has admitted voluntary lessons at some public schools of the related provinces.[5]

Turkic minorities

Bulgarian Turks live in Bulgaria and Turkey. It is an ethnicity formed starting from the 14th-15th century, when the Ottomans conquered Bulgaria, causing Turkish immigration there and converting many Bulgarians to Islam in the following centuries. Today in Bulgaria almost 300 thousand Turks settle in Dobruja (Silistra and Dobrič), in other north-eastern provinces (Razgrad, Šumen and Tărgovište) and those of the harbour cities of Burgas and Varna, while, conversely, Turkey registered a similar amount as people born in Bulgaria.[6] Almost everyone has kept the Islamic religion.

Crimean Tatars are Turkic peoples, too, about 300 thousand people stationed, as well as in Crimea, in the Romanian Dobruja, especially in Constanța area, where they settled in the 13th century. In Crimea, the Tatars, who preserve their language of Qıpçaq Turkic origin, rate 12.6% of the population and have been the largest Muslim minority of Ukraine up to Russian annexation.

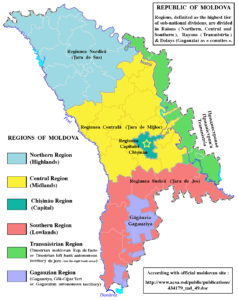

The Gagauzis, people who speak an Oghuz Turkic language and are Christian-Orthodox, owe their current territorial settlement to the flight from Ottoman Bulgaria to Bessarabia in the early 19th century. In fact, today they live between Moldova and Ukraine not far from Transdnestrija borders, mostly (about 160 thousand) in the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia and in the neighbouring districts of Basarabeasca and Taraclia in Southern Moldova. The rest (about 50 thousand) distributes in Ukraine (Budzhak region and Zaporizhia oblast’ on the shores of the Azov Sea) and Turkey. Their traditions, given the Bulgarian roots, go back to a mix of Turko-Balkan morals, and sure, Turkey runs an ethnic-linguistic and cultural leadership, a template for Gagauzis. However, their struggle against the Moldovan government for the promotion of the local language and culture is not very different from the one that Muslim Lazi bring to Turkey.

In Northern Caucasus [fig. 12], settle almost 200 thousand of the above mentioned Karačajs (in Karačaj-Circassia), over 100 thousand Balkars (in Kabardino-Balkaria) and about 40 thousand Nogais (in Stavropol’ Kraj and again in Karačaj-Circassia), all Sunni Muslims. Nogais are heir to Mongol and Turkic tribes that in the 16th and 17th centuries gave birth to the Nogai Horde in the Pontic-Caspian steppe. There are some idiomatic differences between the Nogais from Stavropol’ and those from Karačaj-Circassia, although both speak a Turkic language: the former verbalise in Central Nogai; the latter in Aqnogai (i.e. White or Western Nogai). However, other communities exist in the Romanian city of Constanța and north-western Turkish province of Eskişehir.

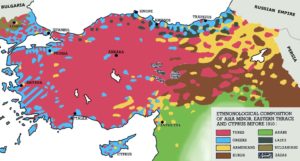

Pontic Greek minorities

In the Black Sea region, there has been a historical Greek presence (colonists from ancient Greece and later from Byzantium), which persists to this day by descent especially in North-East Turkey, in South and East Ukraine, in Georgia and in Brăila and Constanța Romanian districts. The current scarce presence in the area (about 500 thousand people) is still a result of the Ottoman Sultanate collapse after WWI, which led to the diaspora also in the surrounding regions and forced most of the Pontic Greeks to return to their original homeland. The “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations” signed in Lausanne in 1923 involved more than 1.5 million Greeks from Anatolia, Eastern Thrace and the Caucasus exchanged with 355 thousand Muslims from Greece. The Christian-Orthodox exodus has sizably reduced the Christian presence in general because before the Caliphate has expired and the European nationalisms have triggered a disastrous war, Christian people were the majority in many Turkish cities and governments naturally pursued and implemented a religious integration [see fig. 24].[7] Then, the new republic would have launched a “Turkification” and assimilation project.

In present-day Turkey, 4,000 Orthodox Greeks settle in Imbros, Tenedos and Istanbul, around the Sea of Marmara. But on the Black Sea shores there are still Pontic Greeks, who have converted to Islam since the 17th century, and, according to statistics of the current year, number 345 thousand in Rize, Sakarya and Trabzon provinces. The surroundings of the latter city also home to 4,500 Greeks that have kept their Romeyka language in the form of a Pontic Greek dialect but this community is Muslim, as well.

The remaining Pontic Greeks of the diaspora are located mainly on the Black Sea northern coast, namely in Donbass and North Caucasus (Stavropol’ and Krasnodar) but a few thousand also live in Crimea, Odessa and the Georgian Adjara.

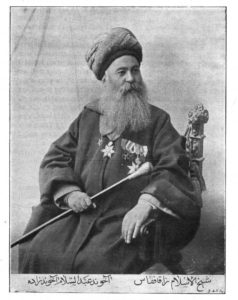

Armenian minorities

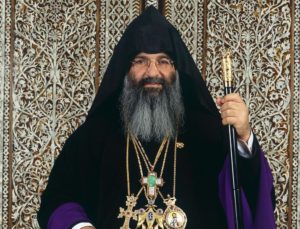

Fig. 16 – Mesrob II Mutafyan, the Armenian Apostolic Church defunct Patriarch of “Istanbul and All of Turkey”

In the Black Sea area, the Armenians of diaspora locate mostly on the east coast. Several thousand members of the oldest communities have settled in the Bulgarian coastal cities of Burgas and Varna since the 5th century as part of the Byzantine cavalry. More than 40 thousand are in Abkhazija (where they rate 20% of the local population), precisely in the capital Sukhumi and in the cities of Gulripshi and Gagra, following the emigration that began in the late 19th century. In Northern Caucasus, Armenians are widespread in the Republic of Adygea, Stavropol’ Kraj and the oblasts of Krasnodar and Rostov-na-Donu. In the southern Georgian region of Samtskhe-Javakheti, on the Armenian border, they make up the people majority and are divided in votaries of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Gregorian Church (80%) and the Armenian Catholic Church (the remaining 20), namely those who accept the Pope of Rome primacy. Civil claims have repeatedly raised the issue of their rights, which, as always in these cases, are about greater respect of national identity and the Armenian language and consequent greater autonomy. Besides that, there are religious demands for the return to the Armenian Apostolic Church of some churches currently owned by the Georgian Orthodox Church. However, despite protests and low participation in the Armenian political life, the authorities have not satisfied their requests (Middel, 2007).

Hemşins, as well, belong to the Armenian ethnicity and are classed into three distinct groups. The Northern Hemşin, mostly Christian, are those living in Georgia and the Caucasus and speak a dialect of the Western Armenian family. Western and Eastern Hemşin establish on the Black Sea eastern coast of Turkey. They, as well as the Georgian Lazi settling on the same areas, have been Sunni Muslims since the second half of the 15th century but immigrated in the early 19th century from Georgia, Russia and parts of Armenia. They share with the Lazi also the status of a minority speaking an endangered archaic language (Kirac, 2019), even though all now speak Turkish fluently.

Other minorities

Many other minorities settle around the Black Sea and, among these, Jewish, Romance, Indo-Aryan and German ethnic families mark their persistent presence.

Ukraine and Turkey (especially Istanbul) record the largest Jewish presence in the area, respectively 53 thousand and 15 thousand people, whose figures increase further if we consider people with Jewish parents.[8] According to the 2014 census, 3,300 Jews live in Crimea and, among them, the members of two small communities with different features and origins. The Crimean K’arajs, who profess the Karaite Judaism loyal to Written Tōrāh as the sole supreme juridical-theological authority, derive from the Turkic-speaking adherents of Central and Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire and inherited from them the Karaim, a Turkic language with Hebrew influences. The Krymchaks are Orthodox Jews heirs to immigrants from all over Europe and Asia and speak a Turkic language, too.

Black Sea people framed in the Romance minorities are Romanians and Moldovans distributed in the countries of the north-western section of the area. The issue becomes more complicated when one considers that many scholars regard Moldovans as part of Romanian ethnicity and therefore do not exist in practice. This is rather a political issue involving the history of Romania and Moldova and the suspicion that the former has always opposed to the Soviet Union after WWII when they were both sharing the same regime ideology. The censuses in Moldova and Transdnestrija, however, record Moldovans as a separate ethnic group but the Moldovan Declaration of Independence in 1991, contrary to the subsequent Constitution, establishes the Romanian as the official language. Beyond these necessary distinctions, Moldova surveyed 193 thousand Romanians and Ukraine 151 thousand. As for the Moldovans outside Moldova, 259 thousand live in Ukraine, 162 thousand immigrated to Romania, and 157 thousand at the 2015 census are the “Moldovan ethnic” citizens who remained in Transdnestrija after the 1990 secession.

The Roma (or Gypsies) are Indo-Aryan people originating from northern India who by their very nature are hard to be surveyed as a unit. Romania, the country hosting the higher number, allocate more than 600 thousand Gypsies but Bulgaria registers the highest percentage of the total local population (more than 10%), while Turkey, Romania and Moldova stand on the 3-4%.

Finally, following the USSR collapse, in the latest 30 years, around 33 thousand Germans coming from Russia and Central Asia gradually settled in the Ukrainian land.

The historical background

This description does not have the intent to treat statistically such a complex topic but just to offer the heterogeneity framework of human presence around the Black Sea we cannot reduce to a bureaucratic context of the more or less recent national membership. Of course, if we accept the perspective of historical continuity and the independence status of any country, the Kievan Rus’, the first nucleus of Greater Russia, was born in 882 and developed later to the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the present Russian Federation; current Romania and Bulgaria formally born in 1881 and 1908; Turkey in 1923 from the dissolution of the Ottoman Sultanate; but USSR-arisen Transdnestrija, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia and Abkhazija have less than 30 years of life as independent states (including the first and last not even universally recognised).

Without minimising the importance of national belonging, it seems clear that a more suitable instrument for understanding social interactions among groups with different customs and traditions is the examination of ethnic-linguistic and religious ties in their historical context and their relationships with the political power at each time. Here we can only propose the premises of such an analysis and indicate some of the historical landmarks that are the spring source of the groups previously summarily analysed.

First, Georgians seem to be the oldest still existent ethnic group in the area, heirs to the Egrisi (Caucasian Colchian tribes) and the Moschians (whom the already mentioned Meskhetians named from) and founders in the 4th century B.C. of the Kingdom of Kartli (or Iberia), the first Georgian state then converted to Christianity by Saint Nino.

Fig. 22 – Kievan Rus’, Icon The Baptism of Russia (1988) by Archimandrite Theodore Zenon, a monk at the Pečerskij Dormition Monastery, in the Pskov oblast’

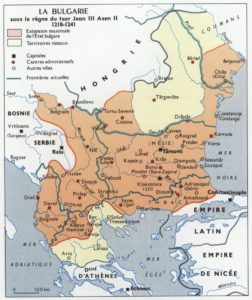

The Bulgarian ethnicity has ancient origins, as well. Great Bulgaria was founded in 632 in the Black Sea northern arc by Onoğur Bulghars, who were Turkic semi-nomadic people from Central Asia. The first Bulgarian State of Proto-Slavic language was born on the territory of present-day Bulgaria in 681, becoming an Empire in 913 and dominating the Balkan area from Dnepr to the Adriatic Sea during the 9th-10th centuries. Christianity had become the state religion since 864 and Islam since 922. Meanwhile, Slavic and Finnish people joint by the Old East Slavic language had founded the Kievan Rus’, which in the 10th and 11th centuries was the largest and most powerful state in Europe. Its Christianisation took place in 988 under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople jurisdiction. It meant not only the Slavic Paganism neglect but the expansion outset of an Eastern Christian sensibility of which nascent Russia is still part since the 1054 East-West Schism in the Church of Rome. The fact that the Grand Prince of Kiev Saint Vladimir the Great had baptised in the ancient Greek colony of Chersonesus, in Crimea, would later create the basis for legitimising Russian power over the area.[9]

In 1227, when the founder of Mongolian Empire Genghis Khan died, the Golden Horde arose, a territory which also included what today is Southern Russia and would soon have reached Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Inevitably, the ethnic blend (Mongol, Mongol Tatar, Turkic and Finno-Ugric groups) led to new physical figures and civilisations, which, according to some theses, Tatars could arise from.[10] As you might expect, the Qıpçaq language spoken by its Khans prevailed and in 1313 Sunni Islam became the state religion.

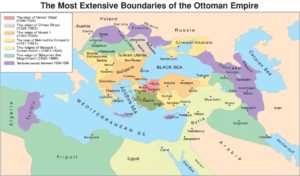

On the southern front, the Ottoman Sultanate, born in 1299 in Anatolia, between 1362 and 1393 took Adrianople, in the Eastern Thrace, Sofia, Šumen and Tărnovo, in current Bulgaria, from the Byzantine Empire: it was the prologue to the Constantinople conquest in 1453 and the beginning of the spread of Islam in South-Eastern Europe. The Crimean peninsula, formerly dominated by local khans of the Geray dynasty since 1441, formally became in 1478 the Crimean Khanate. Although a vassal state of the Ottoman Sultanate, the Khanate was flexible and pragmatic with respect to the Grand Duchy of Moscow, in turn, tributary vassal to the Golden Horde. Under Suleiman the Magnificent’s rule, Western Armenia and Western Georgia entered the Sultanate, and Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia became its tributary principalities.

In general, throughout the Ottoman period, Islam was more tolerant than Christianity was at the time (Jobst, 2017). Just think about the treatment Jews received after the Spanish Reconquista and the resulting open doors policy Istanbul began towards them. Ethnic and religious minorities in Anatolia, as well, lived for centuries alongside the Muslim Turks [fig. 24], creating a behavioural syncretism well away from isolationism or assimilation (Martyn, 2016). However, the same was not true of populations outside the Sultanate, often subjected to raids and looting.

The conquest of vast areas under Ottoman domination during the Russian-Ottoman Wars, witnesses the interest in access to the Black Sea by Russia, which meanwhile ran from the Tsardom of Muscovy to Peter the Great’s Russian Empire. The Crimean Khanate, where the Tatars formed an ethnic majority, snatched from the Ottoman protection in 1774 and, after a glorious history of over three centuries, Russian Empire annexed it in 1783 by Catherine II, which held to specify that the region was to become part of the Russian Empire “forever” (Jobst, 2017). When the Russo-Turkish confrontation culminated in the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, the harsh result was the expulsion of Muslim people from Russian-seized areas to the Ottoman Sultanate. In Crimea, after a lusty policy of colonisation and encouragement to the immigration of different ethnic groups (including Germans, Orthodox Bulgarians and Gagauzis), the Crimean War led to Tatars’ mass flight mainly to Anatolia and Dobruja.

Fig. 27 – United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia: administrative organisation (1856-1878) (by Spiridon Ion Cepleanu, 2014)

In the early 19th century, the Russian expansion reached the Caucasus and in 1801 Saint Petersburg annexed Georgia, snatching it from the Bagrationi dynasty that ruled it from medieval times. The Adjara, the southern coastal region of present-day Georgia, was ceded by the Ottoman Sultanate to Imperial Russia in 1878 at the end of the Russo-Turkish War but its population remained tied, as in part nowadays, to Turkey and Islam. The same year, on the other side of the Black Sea, the Principality of Bulgaria was born as an Istanbul vassal. It was the premise for its independence achieved in 1908. The formation of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, instead, had its natural result in the Kingdom of Romania born in 1881.

With the October Revolution, Ukraine, Georgia and Crimea declared ephemeral independence from Bolshevik Russia. The Ukrainian National Republic and the Democratic Republic of Georgia ran from 1918 to 1921. In Crimea, the Tatars gave rise to the Crimean People’s Republic,[11] the first attempt in the Islamic world to create a secular state. This independent republic had been lasting for one month. But the White Guard, a confederation of anti-communist forces, controlled the territory until 1920 when the Red Army defeated it and began the purges of hundreds of thousand people. They were organised by Hungarian Béla Kun, as he became the head of the Crimean Revolutionary Committee. At the time, the demographic picture of the latest census in Ukraine included among ethnic minorities Russian and Jewish (around 10% each) and a more restricted presence of Germans; in Crimea, the majority of the population was made up of Tatars and Russians (each for over a third), the Ukrainians were 12%, with a smaller presence of Jews and Armenians. Two examples of an ethnic complexity concerning the Black Sea area as a whole and that neither the USSR federative structure nor the Lenin-led nationality policy were able to manage for avoiding future clashes. However, it has to note that the Adjar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, established in 1921 within Soviet Georgia on Russian-Turkish agreement, was an example of autonomy on a religious basis because it protected local Muslims ethnically Georgian. Too bad the USSR had banned religious practice …

During WWII, the Wolgatatarische Legion (the Legion of Volga Tatars) welcomed in the Wehrmacht many volunteers of the non-Russian ethnic groups from the region. Stalin, moreover, accused of collaborationism the Crimean Tatars, because he “forgot” the heavy conditions the occupation of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine with jurisdiction over Crimea from September 1942 to October 1943 had imposed. In 1944 began the communist deportations of Crimean Tatars and Greeks to Siberia and Central Asia (Minahan, 2000) and in 1956 Khrushëv allowed millions of exiled by Stalinist purges to come back to their lands but “forgot” the Tatars. The ethnic, cultural and religious plurality that had characterised the Black Sea northern coast in previous centuries has so lost after WWII. In the meantime, since 1954 Crimea had been ceded to Ukraine, still within the USSR.

With the season of independence after the USSR dissolution, the ideological prejudice towards religions fell, and they were finally free to carry out their function. However, religious and ethnic minorities within the countries began to suffer from the nationalistic policies of new governments, as is the case already mentioned of Georgia in Adjara and Abkhazija or the Gagauzis in Moldova. In Crimea, the establishment of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea as a constituent entity of independent Ukraine sedated the first secessionist attempts, while the Greeks allocated within the borders of the former USSR started their return to Greece.[12] For its part, the Kremlin inaugurated the ethnic policy of defending Russian minorities in other countries of the area, encouraging or causing the secession of Transdnestrija, South Ossetia and Donbass republics and implementing the annexation of Crimea. On the contrary, still today there are on the ground similar attempts from Romania towards the Ukrainian Budzhak [fig. 29], historically belonging to the Bessarabia incorporated by the 1918 Declaration of Alba Iulia [fig. 30], against the pro-Russian tendencies of the Gagauzis of Moldova and the Bulgarians of Budzhak.[13] As evidence, according to press reports,[14] four years ago there was a precarious attempt to establish a Bessarabia People’s Council (BPC), where representatives of the Bulgarian nationalist party Attack were involved. The intent was to establish a Bessarabia People’s Republic, immediately kept down by the Ukrainian authorities and distanced by local Bulgarian communities, but the action raised concerns about Moscow’s desire to create a Novorossija from Bessarabia to Donbass for bringing together Russian-speaking people and further undermine the integrity of the Ukrainian state.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the multi-ethnicity, the poly-linguism and multi-religiosity of the people settled around the Black Sea have historically created reasons for interconnections and, alternatively, of rivalry, invasions and looting. Coexistence is perhaps not congruent with the instincts of oppression cyclically surfacing in groups of power succeeding one another in history and aggregating according to canons of mutual inclusion and resulting exclusion of minorities. This finding is even more evident since the nation-states have replaced the imperial conception of the multiplicity of composition and expression (at least in theory). In ancient times, this conception had allowed Cyrus the Great to free the Jews and the Roman Empire to crown rulers from distant provinces; in more recent times, the Ottoman Sultanate to welcome Christians, Jews and peoples of the most varied ethnic groups and Russian Empire to form, albeit not without conflicts, a State with a hundred ethnic groups and dozens of religions.

Today, the growing nationalisms inaugurated in the 1800s try to simplify the solutions, calling the dominant ethnic groups to unity and creating tensions not only to their neighbours (which is the natural genesis of wars) but within the nations that hardly are ethnically compact. Thus, the problem is on managing minorities and their claims in terms of existing or presumed rights, according to the fundamental laws of the States.

The most striking examples presented here relate to territories of historical formation (Dobruja, Bessarabia, the Western Caucasus), today divided by unnatural boundaries definite by wars for the establishment of national states. These regions are a quintessential mix of cultures settled on the same soil, whose components have the option of following each one a path of independence or, conversely, requiring respect and enhancement of their peculiarities and prerogatives. Quite the opposite of the continuous appeals to conform to the prevailing customs, which implies homogenisation to a majority in terms of traditions, languages, religions and, ultimately, loss of identity and assimilation in return for acceptance.

The variety of the Black Sea peoples must be viewed as an opportunity. The wish is that institutions and civil society give the various countries in the area this hope.

***

[1] Inga Popovaite (March 5th, 2015). Georgian Muslims are strangers in their own country. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/georgian-muslims-are-strangers-in-their-own-country/

[2] Bert Middel (28 August 2007). State and Religion in the Black Sea Region (Draft Report). NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Sub-Committee on Democratic Governance.

[3] Nino Narimanishvili (June 21st, 2017). Return from exile: Muslim Meskhetians from Georgia. Retrieved from https://jam-news.net/the-return-from-exile/

[4] Minority Right Group International (n.d.). Laz. Retrieved from https://minorityrights.org/minorities/laz/

[5] Nimet Kirac (March 19th, 2019). Lost words: The struggle to save Turkey’s disappearing languages. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/lost-words-struggle-save-turkeys-disappearing-languages.

[6] Ministry of Interior, General Directorate of Civil Registration and Nationality, Turkish Statistical Institute (July 6th, 2015). Place of Birth Statistics, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=21505.

[7] Sam Martyn (October 26th, 2016). Turkey’s Christ-Haunted Black Sea Coast. Retrieved from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, http://jenkins.sbts.edu/2016/10/26/turkeys-christ-haunted-black-sea-coast/

[8] Sergio Della Pergola (2017). World Jewish Population, Number 20. Berman Jewish DataBank, New York, NY.

[9] Kerstin Susanne Jobst (2017-02-13). The Northern Black Sea Region. Retrieved from http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/crossroads/border-regions/kerstin-susanne-jobst-the-northern-black-sea-region.

[10] Azade-Ayşe Rorlich (1986). The Volga Tatars. A Profile in National Resilience, 1. The Origins of the Volga Tatars. Retrieved from http://groznijat.tripod.com/fadlan/rorlich1.html#1.14.

[11] James B. Minahan (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut (USA), p. 189.

[12] Eleni Sideri (December 2017). Historical Diasporas, Religion and Identity: Exploring the Case of the Greeks of Tsalka, in Eleni Sideri, Lydia Efthymia Roupakia, Religions and Migrations in the Black Sea Region, pp. 35-56. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39067-3.

[13] European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies, Policy Department (November 2017). Facing Russia’s strategic challenge: Security developments from the Baltic to the Black Sea. doi:10.2861/047170 (pdf).

[14] Thomas de Waal, Balázs Jarábik (May 24th, 2018). Bessarabia’s Hopes and Fears on Ukraine’s Edge. Carnegie Europe, Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from https://carnegieeurope.eu/2018/05/24/bessarabia-s-hopes-and-fears-on-ukraine-s-edge-pub-76445; Adam Roberts (November 20th, 2017). Bulgarian factor in Russian aggression against Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.youreporter.it/foto_bulgarian_factor_in_russian_aggression_against_ukraine/

REFERENCES

- Della Pergola, Sergio (2017). World Jewish Population, Number 20. Berman Jewish DataBank, New York, NY.

- de Waal, Thomas and Jarábik, Balázs (May 24th, 2018). Bessarabia’s Hopes and Fears on Ukraine’s Edge. Carnegie Europe, Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from https://carnegieeurope.eu/2018/05/24/bessarabia-s-hopes-and-fears-on-ukraine-s-edge-pub-76445.

- European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies, Policy Department (November 2017). Facing Russia’s strategic challenge: Security developments from the Baltic to the Black Sea. doi:10.2861/047170 (pdf).

- Jobst, Kerstin Susanne (2017-02-13). The Northern Black Sea Region. Retrieved from http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/crossroads/border-regions/kerstin-susanne-jobst-the-northern-black-sea-region.

- Kirac, Nimet (March 19th, 2019). Lost words: The struggle to save Turkey’s disappearing languages. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/lost-words-struggle-save-turkeys-disappearing-languages.

- Martyn, Sam (October 26th, 2016). Turkey’s Christ-Haunted Black Sea Coast. Retrieved from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, http://jenkins.sbts.edu/2016/10/26/turkeys-christ-haunted-black-sea-coast/

- Middel, Bert (28 August 2007). State and Religion in the Black Sea Region (Draft Report). NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Sub-Committee on Democratic Governance.

- Minahan, James B. (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut (USA).

- Ministry of Interior, General Directorate of Civil Registration and Nationality, Turkish Statistical Institute (July 6th, 2015). Place of Birth Statistics, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=21505.

- Minority Right Group International (n.d.). Laz. Retrieved from https://minorityrights.org/minorities/laz/

- Narimanishvili, Nino (June 21st, 2017). Return from exile: Muslim Meskhetians from Georgia. Retrieved from https://jam-news.net/the-return-from-exile/

- Popovaite, Inga (March 5th, 2015). Georgian Muslims are strangers in their own country. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/georgian-muslims-are-strangers-in-their-own-country/

- Roberts, Adam (November 20th, 2017). Bulgarian factor in Russian aggression against Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.youreporter.it/foto_bulgarian_factor_in_russian_aggression_against_ukraine/

- Rorlich, Azade-Ayşe (1986). The Volga Tatars. A Profile in National Resilience, 1. The Origins of the Volga Tatars. Retrieved from http://groznijat.tripod.com/fadlan/rorlich1.html#1.14.

- Sideri, Eleni (December 2017). Historical Diasporas, Religion and Identity: Exploring the Case of the Greeks of Tsalka, in Eleni Sideri, Lydia Efthymia Roupakia, Religions and Migrations in the Black Sea Region, pp. 35-56. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39067-3.