Beijing public diplomacy towards the antagonism of the great powers, people’s distrust and political elites appeasement

By Glauco D’Agostino

Uzbekistan: Xiva / Khiva (Khorezm), Pahlavon Mahmud Str., Khan Muhammad Amin’s Madrasa and “Kalta” Minaret (author’s photo)

Abstract

The People’s Republic of China opens up to Central Asia and launches its public diplomacy based on its economic potential and a soft power with a friendly face. The Belt and Road Initiative represents today a pillar of Chinese foreign policy, judged successful by many analysts. Beijing would like to develop a Free Trade Area with Central Asia, but Moscow opposes it, fearing Chinese geo-economic dominance. Experts and local academic circles emphasise that the public opinion perceives Chinese influence in a dual way: positively from a geopolitical point of view, to be a bulwark against a growing Western suggestion and the Russian influence; negatively from an identity point of view. In all this, the Western countries, aware of their economic and political weakness in this area, try entering their culture and values, getting in return a precarious consensus from the civil society.

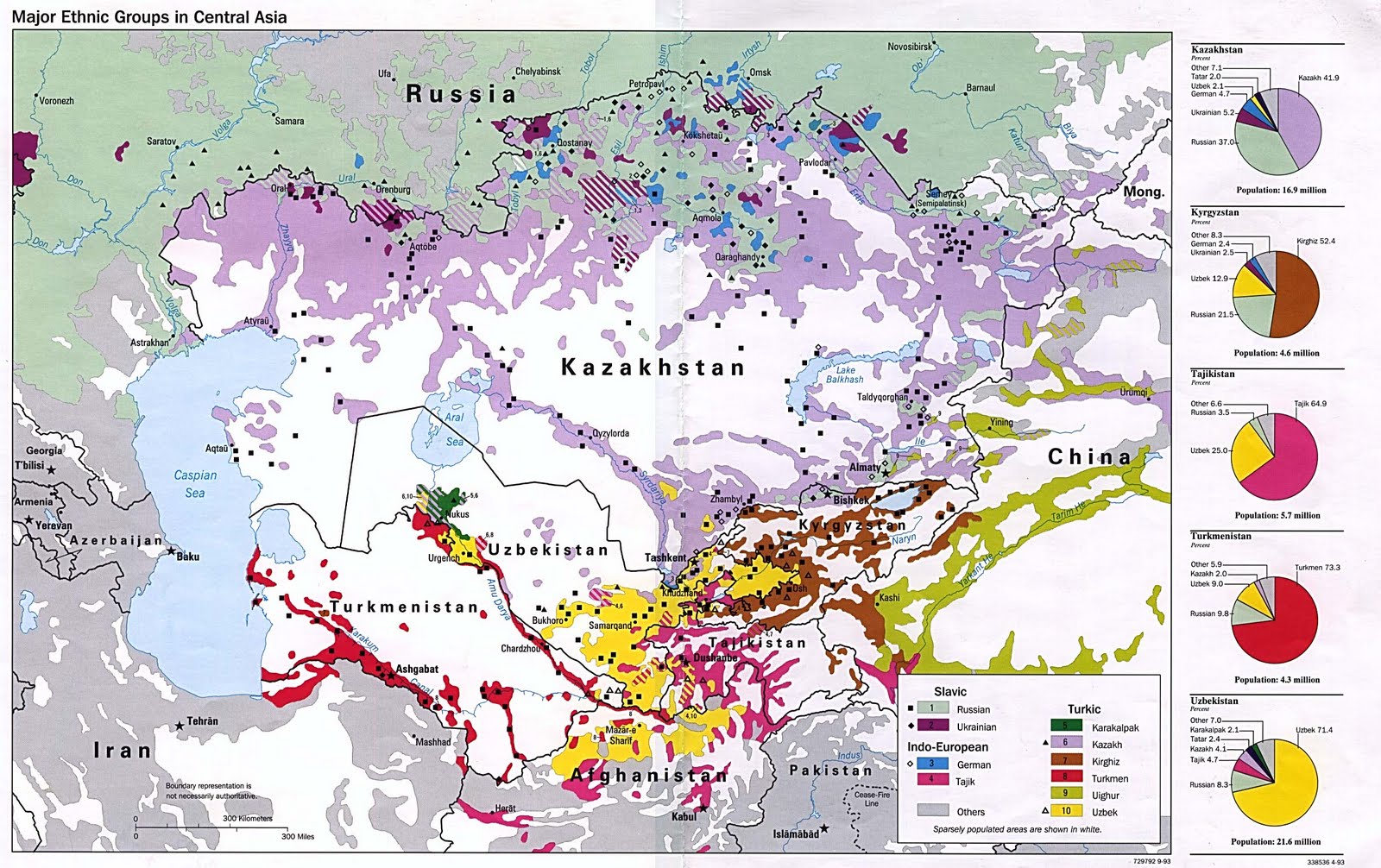

China faces significant problems in Central Asia, with an Islamic structure of large part of the society, the influence of a pan-Turkic archetype, a Russophile orientation of political components, a strong nationalistic flattery and the expansion of a Western behaviour pattern. The geo-political issue of the influence on the Central Asian countries, not only by the great powers but also by some significant regional players, stays in the background. China is arising as an element of mediation among political pressures coming from Pakistan, India, Turkey and Iran, without underestimating the unsolved Afghan question under US aegis.

Keywords: China, Central Asia, public diplomacy, neighbourhood diplomacy, Silk Road Economic Belt, Xīnjiāng.

The pillars of Chinese foreign policy

The Communist Party of China 19th National Congress of October 18th-24th, 2017 included Xi Jinping’s thinking on socialism with Chinese characteristics in the Party Statute. In his first day report, President Xi claimed responsibility for the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative, of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank,[1] of the Silk Road Fund[2]” and the organisation of the “First Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation.” He added: “We should pursue the Belt and Road Initiative as a priority,”[3] and he stressed China entered a development policy with open doors.[4]

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), revealed in 2013 and comprising the terrestrial lines of the “Silk Road Economic Belt” (SREB) and the “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”, represents today a pillar of Chinese foreign policy, judged successful by many analysts. Here the focus is on the SREB,[5] as the main tool of influence (while lacking itself an institutional structure) Beijing would like to exercise on Central Asia, with the geo-political implications investing primarily its closest area in territorial terms (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan border China through its Xīnjiāng Uyghur Autonomous Region). It’s no coincidence the SREB, which was proposed first in 1994 in Kazakhstan by Lĭ Péng, Chinese President at the time, has been announced in September 2013 during a Xi Jinping’s visit to Astana, once again in Kazakhstan, where he had stressed that China has no intention of interfering in the internal affairs of Central Asian nations.[6] In fact, the main strategy embodying its non-interference policy is that, contrary to the behaviour of the so-called “Western” states, Beijing does not subordinate investments to any political reforms,[7] while the Central Asian governments reap a positive economic effect of it without risking the political system stability. Up to March 2017, China had invested US$50 billion and signed contracts for 305 billion for projects along the BRI, and in 2017 the “Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation” announced project funding for a further 80 billion.

Therefore, the People’s Republic of China opens up to Central Asia and launches its public diplomacy based on its economic potential and a soft power with a friendly face, a “neighbourhood diplomacy.”

Other strategies Beijing has chosen to pursue are the following:

- Countering the influence of external major powers;

- Bilateral and regional economic cooperation;

- Solving border disputes;

- Countering terrorism, religious extremism and Uyghur’ independence;

- Contributing to local economies development;

- Multilateral security arrangements.

The EAEU, Chinese energy diplomacy and Xīnjiāng

Beijing has to deal with Moscow, which, at least since first 1999 Putin’s election, has been back to consider the former USSR Central Asian republics as its “backyard”.[8]

Putin and Xi Jinping met in Moscow in May 2015 to coordinate a common space of coexistence between the SREB and the Russian-supported Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU),[9] and next December the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation members had signed a joint declaration in this regard.[10] In July 2017, President Xi, who was visiting Russia, announced an economic cooperation with the EAEU: soon after, the sovereign Russia Direct Investment Fund made known a partnership with the government-owned China Development Bank in order to implement joint projects.[11] However, a different SREB-EAEU approach each towards its Central Asian partners stands up: while the former favours bilateral agreements to facilitate Chinese investments (especially in the energy, infrastructural, commercial and communication sectors), the latter has more a character of a defensive customs union and is structured as cooperation agreed by all its members.[12] This means that, while Beijing does not require a concert of decisions among the partner countries for investment in Central Asia, Moscow needs shared decisions highlighting its leadership, hence raising protectionist barriers, including those hindering China “officious” investments.

The Kremlin centripetal approach does not seem to work if it’s true in recent years mutual exchanges among EAEU members are in freefall.[13] But above all, it does not seem to satisfy the countries having become autonomous from an energy point of view. Turkmenistan (which does not adhere to the EAEU) and Kazakhstan[14] have regained control of their energy production and related transport networks, and show favouring bilateralism among states in ownership and management, largely opening up to Chinese investments and making China their main trading partner.[15] It’s another evidence, yet, of how Beijing soft power based on regional cooperation works. The joint-venture between China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and the Kazakh KazMunayGas gave birth to the 2,200 km-long Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline, which since 2005 has joined the Caspian Sea shores with Xīnjiāng. And the offshore Caspian Sea Kashagan oil field, which since 2013 has been the main source of the pipeline supply, has an 8.4% China stake, although it is not the largest shareholder. The same partnership boosted by Türkmengaz and Uzbekneftegaz enabled the 1,800 km-long Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline system, which since 2009 has linked the Amu Darya right bank, in Turkmenistan, with Xīnjiāng through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.[16]

Xīnjiāng, which is rich in energy and mineral resources and has a strategic economic-industrial structure well organised for intermodality, is always at the strategy heart, from a territorial standpoint. It’s precisely Xīnjiāng that is functional to the overall Chinese design of an opening to the outside: e.g., the 3,000 km-long and US$50 billion-worth China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)[17] launched in 2015, i.e. the set of current US$ 62 billion infrastructure investments aimed at integrating physical and exchange networks between the two countries, will link Xīnjiāng with the southern port of Gwadar, on the Arabian Sea of Balōchistān.[18] According to estimates, over 30,000 Pakistanis are working on the corridor project. Along the CPEC course, China is funding and implementing several mega-infrastructure projects, including road and rail networks and power plants.[19] Other already planned lines of communication to Central Asia will start from Xīnjiāng including, for example, the 500 km-long Kashgar-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbek Ferghana Valley railway through mountains route up to 2,000-3,500 meters above sea level, and requiring the construction of nearly 50 tunnels and more than 90 bridges.[20] This project should connect to the US$1.6 billion Ferghana Valley-Taškent rail link, active since 2016 and partly financed by the state-owned Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank),[21] whose implementation has stalled for political anxieties of the Uzbek government, which fears to enter the Chinese influence area.

The Russian-Chinese relations in Central Asia and the SCO

Since 2001, Beijing-Moscow relations have developed also within a framework of three foreign policy main devices:

- The Treaty of Good-Neighbourliness and Friendly Cooperation Between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation (FCT), a twenty-year strategic tool for diplomatic and geopolitical reliance;[22]

- The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), a resulting regional aggregation of political, economic and security nature (but not a military alliance), replacement of the Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions (Shanghai Five) signed in 1996 by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan;[23]

- The agreement signed in 2007 in Dushanbe, capital of Tajikistan, between SCO and Russia-led CSTO to broaden cooperation on security, crime, and drug trafficking issues.[24]

Today the SCO includes Uzbekistan, Pakistan and India, as well, and communicates with other observer states and dialogue partners; but its structure of peer non-military organisation limits its decision-making and enforcing capacity. Beijing regards it as a tool of a multilateralism is looking for as a stability element (especially to avoid the Xīnjiāng Uyghur centrifugal thrusts), but difficult to use for its policy of authority towards Central Asian countries. On the other hand, it excludes a militarisation policy, as well (its presence is really limited), not only because it concedes a historical military prevalence of Russia in the area, but as an evidence of the non-interference policy it implements in international affairs elsewhere in the world, yet.

All Central Asian countries have no access to the sea and therefore have difficulties in trade relations. Their economic exchanges with China, which the Kremlin had tolerated since the post-Brezhnev era and officially had acknowledged by perestrojka, have always been affected by Moscow-Beijing relations. Moreover, the latter claimed a vast Kazakh territory, Kyrgyzstan as a whole, and a large part of Tajik Pamir.[25] Much of the disputes with the neighbouring Central-Asian republics were defined by treaties signed between 1994 and 2002, although none of them was published giving rise to possible secrecy clauses (Peyrouse, 2016). Today, Beijing would like to develop a Free Trade Area with Central Asia, but Moscow opposes it, fearing Chinese geo-economic dominance among SCO members. The reactions of Central Asian countries are various: the Uzbek government opposes a sharp opposition to it; Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are deterred, as the remittances from millions of workers who emigrated to Russia bind them to Moscow also in foreign policy. This does not prevent an opening by the Kyrgyz entrepreneurs, who regard a Free Trade Area as complementary to the EAEU,[26] while Tajikistan itself has opened not only to investments from China but also from Iran and the Arab Gulf States.

Overall, the Central Asian countries, historically under Russian influence (albeit today with no privileges from an economy assisted by federal subsidies, as in the USSR times) (Dwivedi, 2006), play a balanced role between China and Russia, opening the doors to foreign aid and investment, especially the Chinese ones, while aware of potential cultural and demographic conditioning risks by the near giant. Experts and local academic circles emphasise that the public opinion perceives Chinese influence (first in the commercial rankings, but second following Russia in the cultural ones) in a dual way: positively from a geopolitical point of view, to be a bulwark against a growing Western suggestion and the Russian influence (especially Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, as states facing the Caspian and as oil and gas producers respectively); negatively from an identity point of view.[27]

However, China, which archived much of the file on territorial disputes with neighbours, is using the new openings through the SREB, conceived as a network of bilateral agreements with mutual benefits. This opens up the possibility of establishing a Euro-Asia corridor centred on Central Asia and of interconnecting the economies of the countries in the area. The aim is not new and since 1992 the Asian Land Transport Infrastructure Development (ALTID) project had gathered 32 Asian countries to implement the Asian Highway Network (AH), the Trans-Asian Railway (TAR) and the sub-projects of land transport facilitation, under the UN Economic and Social Commission for the Asia-Pacific (UNESCAP).[28] But SREB’s innovative approach lies right in the bilateral nature of the agreements China has promoted.

The Chinese problems in Central Asia and the Uyghur question

China faces significant problems in Central Asia, with an Islamic structure of large part of the society, the influence of a pan-Turkic archetype, a Russophile orientation of political components, a strong nationalistic flattery and the expansion of a Western behaviour pattern. Without forgetting, among other things, a growing Sino-phobia, which dawns to the point of sometimes invoking polygamy as an identity barrier to the effects of Chinese immigration (Peyrouse, 2016). Therefore, even in the Central Asian countries, a public diplomacy is widely used to orientate attitudes towards China. A Chinese invasion stereotype is used more and more on the Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tajik press, which mounts a criticism to Hàn migration to Xīnjiāng western borders, making cry out to cultural assimilation and attributing to it the aim of breaking the territorial continuity between Uyghurs and Turkic communities of Central Asia.

Ürümqi, Xīnjiāng capital city (photo by M M, 2008)

The Uyghurs, who are ethnically closer to Uzbeks and other Central Asian peoples, are Turkic-speaking Muslims, mostly Sunnis belonging to Ḥanafī theological school of law since IX-X century. Nowadays, Uyghurs established in the Xīnjiāng region are 10-15 million out of 23 million inhabitants residing in the Autonomous Province and 30 million Muslims living in China; out from China, they are about 500,000, mainly living in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, where many representative associations have dissolved by the authorities. The area they inhabit, similarly to what has occurred in Tibet, in the XVIII century fell under the Chinese rule of the Qing Dynasty and later was inherited by the Republic of China in 1912. Especially due to the Three Districts Revolution (Ili, Tarbagatay, Altaj), which had threatened Chinese unity since 1944, that land endured a tighter control following the People’s Republic of China rise in 1949. The communist regime was extremely harsh because of believers’ persecution, State atheism and anti-religious education.[29] After former Soviet states of Central Asia won independence, the Uyghurs of the entire region glimpsed a chance of establishing an “East Turkestan” as a national entity joining again all Central Asian ethnic and speaking Turkic people. Whatever the reason, it’s precisely in Xīnjiāng that over the last twenty years the government has fostered an immigration of Mandarin-speaking Hàn people, indigenous believers of traditional Chinese religions or even atheists, who benefited from the opportunities offered locally in the power or construction industries.[30] The political response of some members of Uyghur society has been the set up of movements, such as:

- The East Turkestan Independence Movements, a galaxy of pro-independence organisations, in fact serving different purposes, from those focusing on Uyghur ethnic identity to those referring to a wider religious identity within the Islamic Umma and even deny an Uyghur ethnicity;

- The Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement, a pan-Islamist organisation active in China since 1997. It would have its organisational base in North Waziristan, Pakistan, and close links with the Afghan-based Islamic Movement of Central Asia and Jund al-Khilāfa (Soldiers of the Caliphate);

- The World Uyghur Congress, a Munich-based international NGO of exiled groups acting inside and outside Xīnjiāng.

However, that China is contributing to the development of local economies has to be recognised. Following its brilliant achievement in energy investments, China is now focusing on the infrastructure and transport sector, mobilising huge resources funded by its powerful banking network and implemented by its state-owned enterprises. But its action riches other branches of the economy, by acting through the following tasks:

- In the credit sector, financing large-scale projects otherwise unsustainable by local banking institutions;

- Providing a pulse to transition from an agricultural and heavy industrial economy towards a tertiary one, resulting in the creation of new jobs in earlier non-existent or under-utilized sectors;

- Supplying markets with low-priced consumer products (according to the purchasing power of most consumers) and technology products (increasingly in demand) for the middle and upper classes.[31]

This Chinese ability to penetrate markets irritates many sensibilities: from the Western countries, which since the independence season have seen a prospect to take possession of those markets; from Russia, which aims at maintaining even now a Central Asian dependence on Moscow, such as in the centralized Soviet system; and from external regional competitors, primarily Turkey and Iran, which think they can win those markets because of ethnic or cultural affinities. Of course, besides any annoyed external countries, there are the Uyghur associations and the local producers, which, following the privatisation of the economy, have faced the market with many difficulties and suffered a contest with stronger and better-organised competitors. This often reflects the protests against Chinese companies of the area, accused of lack of transparency in their activities, to buy the best land (especially in the agricultural sector), to discriminate local workers’ recruitment in favour of Chinese immigrants, or even to prefer those who have occasionally studied in China.[32]

The new public diplomacy of Beijing

In this context, it’s evident that, next to the traditional diplomacy, the new public diplomacy plays supporting the geo-economic policies each country pursues. The targets are almost always the decision-makers and the public opinion of the most promising countries. The players are often non-state actors, supporting interests of a leading State or the global finance, including:

- In the case of China, especially the public companies in the energy sector, led by PetroChina (a subsidiary of China National Petroleum Corporation) and China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation – SINOPEC (a subsidiary of China Petrochemical Corporation). The State at least controls all these companies when does not formally own them. But there are cultural institutions, as well, such as the Confucius Institute, and the state-owned mass media, such as the official press agency Xinhua, the newspaper Renmin Ribao, which is the Chinese Communist Party official newspaper, and the predominant broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV);

- In the case of actors outside the area, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (since 2016 financed also by China) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), all of which fund numerous programs and projects in Central Asia, some assisted by the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB);

- But sometimes the mass media local protagonists, as well.

In Beijing “soft” strategy, all seem to follow the theory of “a harmonious world[33] through ‘voluntary submission [by others] rather than force’ simply through its superior morality and exemplary behaviour.”[34] Undoubtedly, China follows an original way to approach relations. Brian Hocking, Professor of International Relations at Loughborough University, UK, calls it “state-centred, hierarchical model of diplomacy”.[35] The aim is to reverse a trend of China denigration, widespread especially in the Western world, but not only. Ingrid d’Hooghe, Senior Research Associate at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael in The Hague, says “China feels misjudged by the international community, and misrepresented or even demonised by foreign media.” And she goes on: “For these reasons, public diplomacy has become an essential part of China’s foreign policy and diplomacy and the country has invested a lot of time and energy in developing public diplomacy instruments and activities.”[36]

Xi Jinping, in the same 2013 speech announcing the SREB, underlined a need to focus on culture, education and scientific exchanges as tools serving Chinese foreign policy, well aware of an insufficient Chinese access to Central Asia in terms of its image. And more he recommended the use of “people-to-people communications and non-governmental exchanges, laying solid public opinion and social foundations for the development of SCO.” A body that benefited from this highest institutional instruction has been the Confucius Institute, by its nature aimed at aggregating cultural interests around China through the teaching of Mandarin language and Chinese literature, art exhibitions and concerts, TV programs and student exchanges. In Central Asia, the main users of these facilities are in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, but in general, the costs of accessing these opportunities and services are not a secondary impediment. On the other hand, the strategy CCTV implemented in the same countries broadcasting in Chinese or local language seems more effective.[37]

The September 2013 Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in Bishkek. (L-R) Presidents Karimov of Uzbekistan, Nazarbaev of Kazakhstan, Xi of China, Atambaev of Kyrgyzstan, Putin of the Russian Federation and Rakhmon of Tajikistan

Given this organisational effort as a public diplomacy mode, promoting language and Chinese culture in Central Asia has not given its best fruits at the local public opinion, mainly because cultural policy targeted first the ruling class, more inclined and interested in taking advantage of the benefits from the Chinese economic-cultural influence and the resulting investments. This latter finding could bolster the view of those who attribute to the Chinese “harmonious world” a hierarchical nature, because of which “’harmony’ thus becomes ‘elite harmony’”.[38] It’s the effect of a concept that, although you can single out target-States and target-groups, favours among the former the most interesting from an economic point of view and among the latter the groups with a greater influence on decisions, particularly in countries where power is highly centralised as in Central Asia. And it’s a legacy of propaganda methods of the revolutionary regime that concept derives from, even if, to be fair, the removal of that isolationist model is found in today greater openness to international media, dialogue for development, account for successes and failures.[39] But if stakeholders of this process are international business organisations and trusts, little relevance is still granted to public opinions home and abroad. This would also explain the opposition of Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tajik public opinions, which are not involved in Beijing cultural strategy and more sensitive to the respective nationalistic enchantresses.

Conversely, China (along with Russia) has always discretely supported local authoritarian governments and even their repression against the popular protests, such as the one organised in 2005 in Andijon, in the Ferghana Valley, a densely populated and ethnically composite area straddling Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (Dwivedi, 2006). This Valley, a traditional hotbed of the pan-Turanic Basmači rebellion against the Bolsheviks in 1918-34, is still the engine of several Islamist movements, especially those operating in Uzbekistan.[40] However, while an Islamic responsibility for the Andijon protests was excluded as a result, the regime of then-President Islom Abdug’anievič Karimov took advantage on the spot to highlight a danger from Islamist militancy in the country, in order to justify the massacre at an international level. For its part, the SCO dismissed the protests as a terrorist plot.[41] A clear message to Taškent, which has since revised its independence stance in foreign policy claimed in the previous seven years. Just as the pressure on local governments are countless, as when Russian nationalists in Kazakhstan invoked a Kremlin military intervention in 2016 to counteract the popular protests and the terrorist challenge the government has not allegedly been able to control (International Crisis Group, 2017).

The multilateral approach

The appeasement approach based on bilateral agreements does not mean Beijing does not look at large international frameworks to strengthen its leading role as a reference point for the Asian developing countries. Instead, it resorts to this view by an interconnection between various institutions of regional cooperation. We have already mentioned the SCO as a regional aggregation to regulate relations with Moscow. But China also participates on different grounds in the activities of the following organisations or initiatives:

- The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), founded in 2015 and to which China provides one-third of funding;[42]

- The Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), a multi-national forum founded in 1992 for enhancing cooperation towards promoting peace, security and stability in Asia and that held its first Summit in 2002.[43] It signed Memorandums of Understanding with SCO and ASEAN;

- The Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program, established in 1997 [photo below, the CAREC Institute inauguration in Ürümqi in September 2017];[44]

- The East Asia Summit (EAS);[45]

- The United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), established to coordinate the economic, social, and related work of 15 UN specialised agencies. China was elected by the UN General Assembly as an ECOSOC member for the period 2017-19.[46]

China is simultaneously looking for agreements with similar organisations often in competition:

- The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a Russia-led military alliance since 1992 and which today includes, among others, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan;[47]

- The Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), founded in 1985 in Tehrān to improve development and promote trade and investment opportunities;[48]

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)[49] through the ASEAN Plus Three (APT),[50] a forum that began in 1997 to coordinate co-operation between ASEAN and China, Japan and South Korea.

In all this, the Western countries, aware of their economic and political weakness in this area, try entering their culture and values, getting in return a precarious consensus from the civil society due to an apparent resistance to give up a traditional spirituality and to rapidly relinquish a people’s way of life settled through centuries.[51] It also dissatisfies local elites, who regard the calls for the democratisation of society as an attack on their leadership, and the emphasis on the terrorist danger as a pretext to militarise the area. In short, the antithesis of non-interference policy beloved to Beijing. Moreover, the important role of non-state controlled multinational companies and international organizations, which exercise their own public diplomacies, limits the interpretations of those who evoke a “New Great Game” in progress in Central Asia. Also because competition for resources in Central Asia involves new regional powers other than major global powers, such as, for example, those acting on behalf of India, Japan and South Korea (Smith Stegen & Kusznir, 2015).

The geo-political issue

The geo-political issue of the influence on the Central Asian countries, not only by the great powers but also by some significant regional players, stays in the background.

Russia, in addition to the already mentioned strategic interests on Central Asian energy resources, also has the political problem of regional stability and the protection of Russian minorities settled in Central Asia. For this reason, under a CSTO umbrella, the Russian Federation still operates in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, respectively the 201st Military Base in Dushanbe and the Kant Air Base, a naval communication centre 20 km from the capital Bishkek and confirmed in 2013 over a US$500-billion Kyrgyz debt reduction. Furthermore, Moscow provides Astana with all the components of a defensive system (including the air one), inevitably linking it to Russian interests.

Since 2011, the United States has been implementing its own New Silk Road version focused on Central Asia and Afghanistan, especially on the 1,735 km-long Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) in-progress natural gas pipeline, and the Central Asia-South Asia power project (CASA-1000) for the surplus hydroelectricity export from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to Pakistan and Afghanistan.[52] While a military disengagement from Central Asian countries is now foregone,[53] a growing US interest is more than evident as to a stabilisation of Afghanistan (which it occupies militarily) as well as to an opening to India, which from an economic point of view is the second energy-importing country from Central Asia after China[54] and from a political standpoint supports Afghanistan on an anti-Pakistani basis.[55] It’s an attempt to wrest India from the historical Russian influence to create a Kabul-Delhi pro-American axis opposed to the one increasingly close between Beijing and Islamabad, a US ally more and more poised.[56] Meanwhile, both India and Pakistan are members of the SCO, which the Beijing-Moscow agreement rests on, but the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor includes projects in the part of Kashmir Pakistan-ruled de facto and that India claims as its territory.[57] And, it’s sure, the Indian air base at Farkhor, Tajikistan, does not ease a detente, given a Pakistani concern because of the proximity to its borders in terms of minutes of a fly.

In the geo-political question, Turkey role in Central Asia should not be underestimated. The Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States (CCTS),[58] born in 2009 in the Azeri Autonomous Republic of Naxçıvan, welcomes, as well as Turkey, also Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan as the “first voluntary alliance of Turkic states in history”, according to its first Secretary-General words.[59] Among its aims, the ambition of developing common positions among the Turkic-speaking states in the multilateral arena stands out. Now, as regards the two Central Asian countries adhering to it, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are SCO members, but above all Russian-led CSTO and EAEU members. The other two Turkic-speaking countries, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, did not join the organisation by virtue of a neutrality stance, but the cultural influence they experience from Ankara, or better from Istanbul in historical terms, is not to be questioned. However, all of them are also subjects of Chinese “soft power” policy, at least on the basis of ongoing implementation of SREB projects. The cooperation among CCTS countries concerns economy, culture, education, transport, customs and diaspora. Another element of contrast, yet, could just be the diaspora issue because it inevitably involves the Uyghur question. The Uyghurs exiled from Xīnjiāng, we have seen it, live mainly in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Any Turkish patronage on the Uyghur diaspora would certainly challenge the Chinese intransigence to its Central Asian partners about an alleged terrorist threat. But a Beijing-Ankara open clash on these issues is not to be assumed, precisely because the Chinese “soft power” involved Turkey in the New Eurasian Land Bridge as a fundamental part of its geo-strategic western-oriented project.

We can apply the same logic to the Islamic Republic of Iran, given the US$2.2 billion agreement of May 2017 to fund the Tehrān-Mashhad railway project, which China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation (CMC) is in charge of.[60] The Chinese government funded two-thirds of the contract worth, while China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation Sinosure covered related oddment. The route would establish a suitable basis for goods and energy transport between Iran and China, which have set up a long-term bilateral trade target of US$600 billion a year.[61]

So, China is arising as an element of mediation among political pressures coming from Pakistan, India, Turkey and Iran, without underestimating the unsolved Afghan question under US aegis. Also on these matters, China requires a public diplomacy the national public opinions would perceive as a “distinctive element” compared to the poor management so far implemented in Central Asia both in crises and normal governance of economy and development.

[1] It’s a multilateral development bank starting operations in January 2016 with a mission to improve social and economic outcomes in Asia and beyond. Retrieved from AIIB, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (n.d.), https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/index.html.

[2] It was born in 2014 with a Chinese funding of US$40 billion increased by 15 billion in 2017. The Fund “provides investment and financing support for trade and economic cooperation and connectivity under the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative.” Retrieved from Silk Road Fund (n.d.), Purpose and Objectives, http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/enweb/23775/23767/index.html#homezd.

[3] Full text of Xi Jinping’s report at 19th CPC National Congress (04-11-2017). Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-11/04/content_34115212.htm, I The Past Five Years: Our Work and Historic Change and 6. Making new ground in pursuing opening up on all fronts.

[4] “China will actively promote international cooperation through the Belt and Road Initiative. In doing so, we hope to achieve policy, infrastructure, trade, financial, and people-to-people connectivity and thus build a new platform for international cooperation to create new drivers of shared development.” Ibid., XII Following a Path of Peaceful Development and Working to Build a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind.

[5] Particularly, on the New Eurasian Land Bridge, that is the SREB southern branch. It’s a long corridor from Xī’ān (Shaanxi Chinese Province) to Lánzhōu (Gānsu Province), Ürümqi and Qorğas (Xīnjiāng) towards Kazakhstan to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Czech Republic, Germany and Netherland. The other branch is that one connected to the historical northern Trans-Siberian Railway.

[6] Michelle Witte (September 11th, 2013). Xi Jinping Calls For Regional Cooperation Via New Silk Road. Retrieved from https://astanatimes.com/2013/09/xi-jinping-calls-for-regional-cooperation-via-new-silk-road/

[7] Karen Smith Stegen & Julia Kusznir (April 2nd, 2015). Outcomes and strategies in the ‘New Great Game’: China and the Caspian states emerge as winners. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 6 (2015), pp. 100-102.

[8] Arif Bağbaşlıoğlu (2014). Beyond Afghanistan NATO’s partnership with Central Asia and South Caucasus: A tangled partnership? Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 5 (2014), p. 96.

[9] It was founded in 2014 and has started operations since the following year. In addition to Russia, includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Retrieved from EAEU, Eurasian Economic Union (n.d.), http://www.eaeunion.org/?lang=en#about.

[10] Li Xin (November 2016). Chinese Perspective on the Creation of a Eurasian Economic Space. Valdai Discussion Club Report, Moscow, p. 9.

[11] Max Seddon (July, 4th, 2017). Russia, China form $10bn investment fund. Retrieved from Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/e863b62f-1bb2-3a91-869b-e2f11984e0df.

[12] President Putin has proposed the idea of a supranational union among all former Soviet countries (except the Baltic’). As for the Central Asian States, Kazakhstan (an EAEU member) barred a move towards political integration, Tajikistan has so far shown just a general interest and Uzbekistan doubts about integration within such a perspective. Turkmenistan, following its own constitutional stance of UN-recognised permanent neutrality, does not join any regional organisation.

[13] International Crisis Group (July 27th, 2017). Central Asia’s Silk Road Rivalries, in Europe and Central Asia Report N°245, Brussels, Belgium, Executive Summary.

[14] Since 2007 Kazakhstan had strengthened the state-owned KazMunayGas (KMG) company shareholding against Western and Chinese investors in the sector.

[15] Kazakhstan and China signed over twenty energy deals worth US$30 billion. Just about this Chinese record, many Kazakh analysts cast doubt on the contracts correctness, their long-term profitability and environmental risks not adequately assessed. In turn, Turkmenistan exports half of its production to China, after having suspended sales to Russia and Iran.

[16] K. Smith Stegen & J. Kusznir (2015). Outcomes and strategies in the ‘New Great Game’, cit., pp. 101-102.

[17] Part of the 2016-2020 13th Chinese five-year plan.

[18] Glauco D’Agostino (August 30th, 2016). China: A Communism with Anti-Muslim Repressions and … a Hyper-Capitalist Development. Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/china-communism-with-anti-muslim-repressions-and-hyper-capitalist-development/

[19] Among them, the China-Pakistan Karakoram Highway, the highest paved international road in the world (up to 4,693 meters above sea level).

[20] Kamila Aliyeva (December 27th, 2017). China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan to mull railway construction. Retrieved from https://www.azernews.az/region/124688.html.

[21] P. K. Balachandran (October 7th, 2017). China and Russia struggle to gain control over Central Asia. Retrieved from http://www.ft.lk/columns/China-and-Russia-struggle-to-gain-control-over-Central-Asia/4-641055.

[22] Ramakant Dwivedi (November 2006). China’s Central Asia Policy in Recent Times. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Volume 4, No. 4 (2006), p. 145.

[23] Sébastien Peyrouse (2016). Discussing China: Sinophilia and sinophobia in Central Asia. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2016), p. 16.

[24] Valerie A. Pacer (2016). Russian Foreign Policy under Dmitry Medvedev, 2008-2012. Routledge, New York, NY, p. 23.

[25] In July 1986 Mikhail Gorbačëv, at the time CPSU General-Secretary, opened with the Vladivostok Initiative the chance to set out of the USSR-People’s Republic of China territorial disputes dating back to alleged annexations by the Tsarist Russian Empire. Retrieved from R. Dwivedi (2006), China’s Central Asia Policy in Recent Times, cit., p. 140.

[26] International Crisis Group (2017). Central Asia’s Silk Road Rivalries, cit., p. 22.

[27] S. Peyrouse (2016). Discussing China, cit., p. 19.

[28] Nicola P. Contessi (2016). Central Asia in Asia: Charting growing trans-regional linkages. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2016), p. 5.

[29] G. D’Agostino (2016). China: A Communism with Anti-Muslim Repressions and … a Hyper-Capitalist Development, cit.

[30] Several analysts think (and the very Uyghur perception is) this led migration may have been planned to soften the ethnic and religious identity in the Autonomous Province, especially in major urban centres.

[31] S. Peyrouse (2016). Discussing China, cit., p. 17.

[32] International Crisis Group (2017). Central Asia’s Silk Road Rivalries, cit., p. 12.

[33] This concept refers to what Hu Jintao, Chinese President at that time, said in 2005 at the UN 60th Anniversary Summit. Retrieved from R. E. Poole (2014), China’s ‘Harmonious World’ in the Era of the Rising East, in Inquiries Journal / Student Pulse, Vol. 6 No. 10.

[34] Astrid Nordin (May 2014). Radical Exoticism: Baudrillard and Others’ Wars, in The International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Special Issue Baudrillard and War, Vol. 11, No. 2.

[35] Brian Hocking (2005). Rethinking the ‘New’ Public Diplomacy, in Jan Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy. Soft Power in International Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, N.Y., Part I The New Environment, p. 29.

[36] Madariaga College of Europe Foundation (January 13th, 2015). The rapid development of China’s public diplomacy: What does it mean for Europe? Madariaga Report, Brussels, Belgium, p. 2.

[37] Diana Gurbanmyradova (2015). The Sources of China’s Soft Power in Central Asia: Cultural Diplomacy. Central European University, Department of International Relations and European Studies, Budapest, Hungary, pp. 25-37.

[38] R. E. Poole (2014), China’s ‘Harmonious World’ in the Era of the Rising East, cit.

[39] Ingrid d’Hooghe (2005). Public Diplomacy in the People’s Republic of China, in Jan Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy, cit., Part II Shifting Perspectives, pp. 88-105.

[40] Glauco D’Agostino (November 3rd, 2013). The Islamic Revival in Central Asia. Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/islamic-revival-central-asia/

[41] It was not the only massacre by local governments, as in recent years you can number at least two more, albeit differently originated: the first in 2011 in Zhanaezen, the oil-producing city of Kazakhstan near the Caspian Sea; and the other in 2012 in Gorno-Badakhshan, a semi-autonomous province of Tajikistan.

[42] Current events, members are 61 (Regional Members: 40, Non-Regional Members: 21) and 23 other countries have been approved as Prospective Members. Retrieved from AIIB, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (n.d.), cit.

[43] In addition to China and Russia, membership includes almost all the countries of Central and Southern Asia (less than Turkmenistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Malaysia), of Indochina (less than Laos), many Middle-Eastern Countries, Mongolia and South Korea. Retrieved from CICA, Secretariat of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (n.d.), About CICA, http://www.s-cica.org/page.php?page_id=7&lang=1.

[44] In addition to China, membership includes all five Central Asian States, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Mongolia. Retrieved from CAREC (n.d.), CAREC Countries, http://www.carecprogram.org/index.php?page=carec-countries.

[45] In addition to China, membership includes all ASEAN countries, Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and, since 2011, Russia and the United States. Retrieved from ADB, Asian Development Bank, Asia Regional Integration Center (n.d.), East Asia Summit (EAS), https://aric.adb.org/initiative/east-asia-summit-(eas).

[46] ECOSOC 70, United Nations Economic and Social Council (n.d.). Members. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/ecosoc/en/content/members.

[47] The Alliance, which also includes Armenia and Belarus, welcomed Uzbekistan as a full member in 1994-99 and, after the Andijon massacre, 2006-12. Retrieved from Организация Договора о коллективной безопасности (Collective Security Treaty Organization) (n.d.), Basic facts, http://www.odkb.gov.ru/start/index_aengl.htm.

[48] In addition to Iran, Pakistan and Turkey as founding countries, membership includes all the Central-Asian Republics, Afghanistan and Azerbaijan. Retrieved from Economic Cooperation Organization (n.d.), Member States,

http://eco.int/index.php?module=cdk&func=loadmodule&system=cdk&sismodule=user/content_view.php&sisOp=view&ctp_id=23&cnt_id=85059&id=3403.

[49] Born in 1967 in the name of Pan-Asianism, it includes Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. Retrieved from Association of Southeast Asian Nations (n.d.), ASEAN Member States, http://asean.org/asean/asean-member-states/

[50] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (n.d.). ASEAN Plus Three. Retrieved from http://asean.org/asean/external-relations/asean-3/

[51] China minister warns against seduction of values by Western nations (November 17th, 2017). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-politics-culture/china-minister-warns-against-seduction-of-values-by-western-nations-idUSKBN1DH0AU.

[52] Jeffrey Mankoff (January 2013). The United States and Central Asia after 2014. CSIS, Center for Strategies and International Studies, Washington, DC, p. 5.

[53] The US quitted the Uzbek air base in Karshi-Khanabad in 2005 (after the Andijon massacre) and the Kyrgyz one in Manas (just 200 km from the Chinese border) in 2014 at the behest of then-President Almazbek Atambaev. As for the other bases of NATO countries in Central Asia, the French one in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, was evacuated in 2013 and Germany’s in Termez, Uzbekistan, was left in 2015.

[54] Ambrish Dhaka (2014). Factoring Central Asia into China’s Afghanistan policy. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 5 (2014), p. 101.

[55] It should be noted that India has favoured the Afghanistan entry into the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), a kind of geopolitical organisation including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, as well. Furthermore, “India has undertaken several important construction projects in Afghanistan. They built the strategic Zaranj-Delaram highway, which connects Afghanistan with the Iranian port of Chabahar, thus lessening Afghanistan’s dependence on the port in Karachi.” Retrieved from Shazad Ali (March 27th, 2014), India: jostling for geopolitical control in Afghanistan, https://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/shazad-ali/india-jostling-for-geopolitical-control-in-afghanistan.

[56] Asif Aziz (October 29th, 2017). Afghanistan Challenge: Washington-Kabul-New Delhi Axis is Unlikely to Succeed. Retrieved from https://astutenews.com/2017/10/29/afghanistan-challenge-washington-kabul-new-delhi-axis-is-unlikely-to-succeed/

[57] Ivan Lidarev (January 4th, 2018). 2017: A Tough Year for China-India Relations. Retrieved from The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/2017-a-tough-year-for-china-india-relations/

[58] Republic of Turkey, Minister of Foreign Affairs (n.d.). The Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States. Retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turk-konseyi-en.en.mfa.

[59] Rusif Huseynov (23.07.2017). Azerbaijan – Kazakhstan relations: current situation and prospects. Retrieved from Przegląd Politologiczny, Political Science Review, http://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/pp/article/view/10648/10236.

[60] As a subsidiary of China General Technology Group, CMC is an international engineering contractor in transport infrastructure, industrial and power plants. In 2014, the company, in partnership with China Railway Construction Corporation and Turkish companies, built the Ankara-Istanbul high-speed railway.

[61] Saeed Jalili (June 14th, 2017). Iran, China Team Up on New Silk Road Project. Retrieved from https://financialtribune.com/articles/domestic-economy/66450/iran-china-team-up-on-new-silk-road-project.

References

- ADB, Asian Development Bank, Asia Regional Integration Center (n.d.). East Asia Summit (EAS). Retrieved from https://aric.adb.org/initiative/east-asia-summit-(eas).

- AIIB, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/index.html.

- Aliyeva, Kamila (December 27th, 2017). China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan to mull railway construction. Retrieved from https://www.azernews.az/region/124688.html.

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (n.d.). ASEAN Member States. Retrieved from http://asean.org/asean/asean-member-states/

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (n.d.). ASEAN Plus Three. Retrieved from http://asean.org/asean/external-relations/asean-3/

- Aziz, Asif (October 29th, 2017). Afghanistan Challenge: Washington-Kabul-New Delhi Axis is Unlikely to Succeed. Retrieved from https://astutenews.com/2017/10/29/afghanistan-challenge-washington-kabul-new-delhi-axis-is-unlikely-to-succeed/

- Bağbaşlıoğlu, Arif (2014). Beyond Afghanistan NATO’s partnership with Central Asia and South Caucasus: A tangled partnership? Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 5 (2014).

- Balachandran, P. K. (October 7th, 2017). China and Russia struggle to gain control over Central Asia. Retrieved from http://www.ft.lk/columns/China-and-Russia-struggle-to-gain-control-over-Central-Asia/4-641055.

- CAREC (n.d.). CAREC Countries. Retrieved from http://www.carecprogram.org/index.php?page=carec-countries.

- China minister warns against seduction of values by Western nations (November 17th, 2017). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-politics-culture/china-minister-warns-against-seduction-of-values-by-western-nations-idUSKBN1DH0AU.

- CICA, Secretariat of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (n.d.). About CICA. Retrieved from http://www.s-cica.org/page.php?page_id=7&lang=1.

- Contessi, Nicola P. (2016). Central Asia in Asia: Charting growing trans-regional linkages. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2016).

- D’Agostino, Glauco (November 3rd, 2013). The Islamic Revival in Central Asia. Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/islamic-revival-central-asia/

- D’Agostino, Glauco (August 30th, 2016). China: A Communism with Anti-Muslim Repressions and … a Hyper-Capitalist Development. Retrieved from Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/china-communism-with-anti-muslim-repressions-and-hyper-capitalist-development/

- Dhaka, Ambrish (2014). Factoring Central Asia into China’s Afghanistan policy. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 5 (2014).

- d’Hooghe, Ingrid (2005). Public Diplomacy in the People’s Republic of China, in Jan Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy. Soft Power in International Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, N.Y.

- Dwivedi, Ramakant (November 2006). China’s Central Asia Policy in Recent Times. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Volume 4, No. 4 (2006).

- EAEU, Eurasian Economic Union (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.eaeunion.org/?lang=en#about.

- Economic Cooperation Organization (n.d.). Member States. Retrieved from http://eco.int/index.php?module=cdk&func=loadmodule&system=cdk&sismodule=user/content_view.php&sisOp=view&ctp_id=23&cnt_id=85059&id=3403.

- ECOSOC 70, United Nations Economic and Social Council (n.d.). Members. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/ecosoc/en/content/members.

- Full text of Xi Jinping’s report at 19th CPC National Congress (04-11-2017). Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-11/04/content_34115212.htm.

- Gurbanmyradova, Diana (2015). The Sources of China’s Soft Power in Central Asia: Cultural Diplomacy. Central European University, Department of International Relations and European Studies, Budapest, Hungary.

- Hocking, Brian (2005). Rethinking the ‘New’ Public Diplomacy, in Jan Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy. Soft Power in International Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, N.Y.

- Huseynov, Rusif (23.07.2017). Azerbaijan – Kazakhstan relations: current situation and prospects. Retrieved from Przegląd Politologiczny, Political Science Review, http://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/pp/article/view/10648/10236.

- International Crisis Group (July 27th, 2017). Central Asia’s Silk Road Rivalries, in Europe and Central Asia Report N°245, Brussels, Belgium.

- Jalili, Saeed (June 14th, 2017). Iran, China Team Up on New Silk Road Project. Retrieved from https://financialtribune.com/articles/domestic-economy/66450/iran-china-team-up-on-new-silk-road-project.

- Lidarev, Ivan (January 4th, 2018). 2017: A Tough Year for China-India Relations. Retrieved from The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/2017-a-tough-year-for-china-india-relations/

- Madariaga College of Europe Foundation (January 13th, 2015). The rapid development of China’s public diplomacy: What does it mean for Europe? Madariaga Report, Brussels, Belgium.

- Mankoff, Jeffrey (January 2013). The United States and Central Asia after 2014. CSIS, Center for Strategies and International Studies, Washington, DC.

- Nordin, Astrid (May2014). Radical Exoticism: Baudrillard and Others’ Wars, in The International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Special Issue Baudrillard and War, 11, No. 2.

- Pacer, Valerie A. (2016). Russian Foreign Policy under Dmitry Medvedev, 2008-2012. Routledge, New York, NY.

- Peyrouse, Sébastien (2016). Discussing China: Sinophilia and sinophobia in Central Asia. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2016).

- Poole, R. E. (2014), China’s ‘Harmonious World’ in the Era of the Rising East, in Inquiries Journal / Student Pulse, Vol. 6 No. 10.

- Republic of Turkey, Minister of Foreign Affairs (n.d.). The Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States. Retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turk-konseyi-en.en.mfa.

- Seddon, Max (July 4th, 2017). Russia, China form $10bn investment fund. Retrieved from Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/e863b62f-1bb2-3a91-869b-e2f11984e0df.

- Shazad, Ali (March 27th, 2014). India: jostling for geopolitical control in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/shazad-ali/india-jostling-for-geopolitical-control-in-afghanistan.

- Silk Road Fund (n.d.). Purpose and Objectives. Retrieved from http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/enweb/23775/23767/index.html#homezd.

- Smith Stegen, Karen & Kusznir, Julia (April 2nd, 2015). Outcomes and strategies in the ‘New Great Game’: China and the Caspian states emerge as winners. Hanyang University, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Journal of Eurasian Studies 6 (2015).

- Witte, Michelle (September 11th, 2013). Xi Jinping Calls For Regional Cooperation Via New Silk Road. Retrieved from https://astanatimes.com/2013/09/xi-jinping-calls-for-regional-cooperation-via-new-silk-road/

- Xin, Li (November 2016). Chinese Perspective on the Creation of a Eurasian Economic Space. Valdai Discussion Club Report, Moscow.

- Организация Договора о коллективной безопасности (Collective Security Treaty Organization) (n.d.). Basic facts. Retrieved from http://www.odkb.gov.ru/start/index_aengl.htm.